TOP STORIES

ACTIVISM

Chris Hedges: Sermon for Gaza

This sublime madness is the essential quality for a life of resistance. It is the acceptance that when you stand with the oppressed you will be treated like the oppressed. It is the acceptance that, although empirically all that we struggled to achieve during our lifetime may be worse, our struggle validates itself.

MEDIA

Patrick Lawrence: University—An Attack on Intelligence

Will someone explain why we hear daily about all this antisemitism but cannot see anything of it more than the odd, unalarming case—the everyday here-and-there variety? Someone, anyone?

Glenn Greenwald: Matt Taibbi on How “Free Speech” Turned Into a “Far Right” Slogan

Is Big Tech independent? How and why the mainstream corporate media (MSM) is establishment and what that means.

MILITARISM

Modernizing Nuclear War, by Joel Weisberg

Modern nuclear warheads, which the new delivery systems will be hosting, release far more energy than did the original bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Here’s Why U.S. Elites Support Israel No Matter What

Israel has received 30% of all US foreign aid. Since World War II they get about $4 billion every year and have received almost 300 billion since 1945. When you adjust for inflation which is enough money to end world hunger.

VOICES

Judaism and Zionism, by Sue Ann Martinson

Israel has taken the position that it is innocent of any wrongdoing even though at minimum since Nakba in 1948 they have perpetrated an apartheid neo-fascist state...with use of...tactics borrowed from their previous oppressors in Nazi Germany. And now they have adopted GENOCIDE, as they systematically bomb and destroy Gaza.

Three on Gaza: Minnesota Divest, Communicating with Gaza, Palestinian Bibliography

Not another nickel, not another dime, no more money for Israel’s war crimes!

ECOLOGY

Rejecting the Facade: Unveiling the Ecological Toll of War and Genocide,

At the heart of this destructive cycle lies a perverse economic incentive, where war becomes a lucrative business at the expense of both people and the planet.

A Life on Our Planet: David Attenborough (video)

David Attenborough's take on a simple solution to ease if not halt the climate crisis. If only those who have control of the political system would listen instead of being involved in petty politics and pushing more and more fossil fuel sources and use. And of course all that money that is going to the military that could be used to stop the wars, save the earth and in the process most likely the human race and all creation.

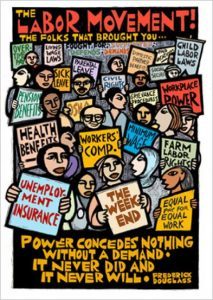

ECONOMY

Billionaires are pillaging America. How do we fight back? | The Chris Hedges Report

This latest attack on the rights of workers is the culmination of a decades-long assault on the working class in the US, which has been caught between an economic system hemorrhaging jobs and a political system that refuses to address their problems.

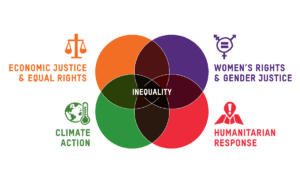

EQUAL RIGHTS

Student Protests and the Rise of U.S. Authoritarianism, by Thad Baltimore

At the heart of student protest demands is the divestiture of university finances from companies profiting from Israel’s illegal occupation in Palestine. This points to one reason university presidents are resistant to student demands — the corporatization of universities.

POLITICS

SWLRT SNAFU: Southwest Light Rail Train—Situation Normal All “Fouled” Up

The over-budget will be paid exclusively by Hennepin County taxpayers. Hennepin County’s 2023 population was 1,320,307. With a $1,000,000,000 debt that would be about $1,000 of “cost-sharing” owed by each man, woman and child in the county. SWLRT SNAFU: Southwest Light Rail Train—Situation Normal All “Fouled” Up Skybridge pedestrian walkway More

Jeffrey Sachs: The Failures of the Global Economic System, World Warming, Nuclear Age, Peace

There's nothing in the global economic system that automatically protects the environment, How can we cooperate to achieve the objectives.

Subscribe via email

Enter your email address to follow Rise Up Times and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Oh, sacred world now wounded,

we pledge to make you free,

of hate, of war, and selfish cruelty,

and here in our small corner

we plant a tiny seed,

and it will grow to beauty

to shame the face of greed.

Pete Seeger

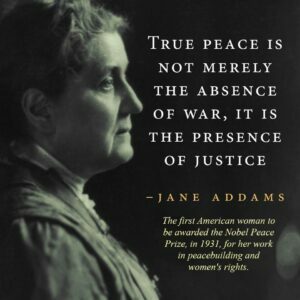

Jane Addams was the first American woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Throughout her life, Addams struggled not only for women’s rights, but also for labor and civil rights, free speech and world peace.

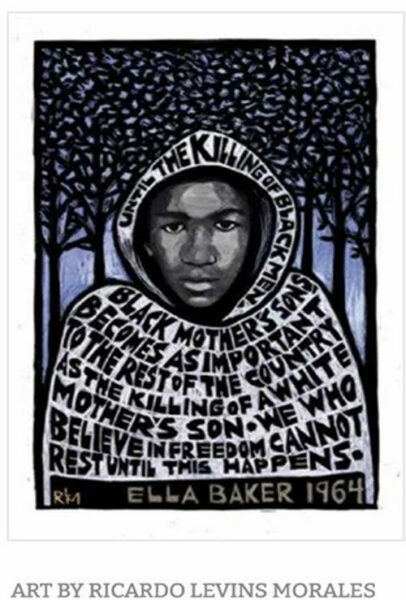

BLACK LIVES MATTER