Editor’s Note: I attended Margaret Fuller elementary school from second through sixth grade. But were we never told who the school was named after or why. It was not exactly a forbidden subject, just never brought up, I assume because I attended before the 1970s wave of feminism. Built in 1896, the school served many generations of South Minneapolis elementary school students. The school was torn down and the land converted to Fuller Park in 1977. This small park, a center of community life, offers many activities and features a flower garden.

From Tangletown News Fall 2012 Edition

Margaret Fuller Elementary School was erected in 1896 by the city of Richfield and cost $8,000. The school was designed by architect Harry W. Jones, who also designed the notable Tangletown Water Tower and several homes in the neighborhood. Tangletown’s resident historian, Tom Balcom, was approached to put together a complete history, now available to everyone at the park.

Photo Minneapolis

Public Schools

Who was Margaret Fuller?

By Tjody deVaal

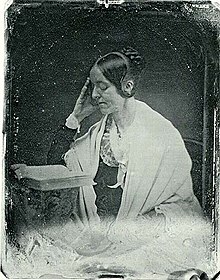

Both Margaret Fuller Elementary School and Fuller Park are named for this woman. It turns out she was quite amazing.

Margaret Fuller, born in 1810, lived a rich, complex, creative, and much-too-short life. She was a contemporary of Emerson and Thoreau, fluent in Latin, Greek, German, French, and Italian. She published six books in all during her lifetime when the American publishing industry was still in it’s infancy. At age 24 she assumed editorship of The Dial, The New Yorker of its day. At age 34 she was the first woman in America to have a front page by-line and her essays were widely published and highly regarded by the intelligensia of her day. While working at Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, she was sent to Europe as the first woman foreign correspondant.

Margaret was a vocal proponant of womens’ rights to jobs and education. She is best known for an essay she wrote in 1843. Her essay explored the nature of both men and women, she said. “Man” could not fulfill his potential, she believed, until “Woman” fulfilled hers. Heady stuff for its time when mere whisper of women’s rights set off alarms. Fuller wanted it all for women—as thinkers, voters, governors, carpenters, mothers, and anything else they desired—and she wanted it all for men.

When Margaret, her husband, Marquis Giovanni Ossoli (while in Rome, she married the impoverished Italian nobleman fighting against the Papists), and their little son, Nino, sailed back to the U.S. from Italy in the summer of 1850, the ship got caught in a storm one hundred fifty yards off the coast of Fire Island, New York, hit a sandbar, and broke up. Those on shore watched the ship go down and the last passengers with it, including Fuller. Neither her body or Ossoli’s was found; their young son is buried at Mount Aubern, Massachusetts. Sadly, her manuscripts from the years in Italy went down too, never to be recovered.

Margaret Fuller: From Wikipedia

Sarah Margaret Fuller Ossoli (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850), commonly known as Margaret Fuller, was an American journalist, critic, and women’s rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movement. She was the first full-time American female book reviewer in journalism. Her book Woman in the Nineteenth Century is considered the first major feminist work in the United States.

Born Sarah Margaret Fuller in Cambridge, Massachusetts, she was given a substantial early education by her father, Timothy Fuller. She later had more formal schooling and became a teacher before, in 1839, she began overseeing what she called “conversations”: discussions among women meant to compensate for their lack of access to higher education. She became the first editor of the transcendentalist journal The Dial in 1840, before joining the staff of the New York Tribune under Horace Greeley in 1844.

By the time she was in her 30s, Fuller had earned a reputation as the best-read person in New England, male or female, and became the first woman allowed to use the library at Harvard College. Her seminal work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, was published in 1845. A year later, she was sent to Europe for the Tribune as its first female correspondent. She soon became involved with the revolutions in Italy and allied herself with Giuseppe Mazzini. She had a relationship with Giovanni Ossoli, with whom she had a child. All three members of the family died in a shipwreck off Fire Island, New York, as they were traveling to the United States in 1850. Fuller’s body was never recovered.

Born Sarah Margaret Fuller May 23, 1810 Cambridgeport, Massachusetts, U.S.

Born Sarah Margaret Fuller May 23, 1810 Cambridgeport, Massachusetts, U.S.

Died July 19, 1850 (aged 40). Off Fire Island, New York, U.S.

Occupation: Teacher, Journalist, Critic,

Literary movement Transcendentalism

Signature

Fuller was an advocate of women’s rights and, in particular, women’s education and the right to employment. She also encouraged many other reforms in society, including prison reform and the emancipation of slaves in the United States. Many other advocates for women’s rights and feminism, including Susan B. Anthony, cite Fuller as a source of inspiration. Many of her contemporaries, however, were not supportive, including her former friend Harriet Martineau. She said that Fuller was a talker rather than an activist. Shortly after Fuller’s death, her importance faded; the editors who prepared her letters to be published, believing her fame would be short-lived, censored or altered much of her work before publication.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Like many other independent news and media sites, Rise Up Times has noticed a decline in the number of people looking at articles due to censorship by Google and Facebook. Independent journalism has become the last bastion in seeking and telling the truth as government and corporate lies are promoted by the mainstream corporate media. Please support us now and share articles widely in these Rise Up Times if you believe in democracy of the people, by the people, and for the people. The people, Yes!

Sue Ann Martinson, Editor, Rise Up Times

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

The contents of Rise Up Times do not necessarily reflect the views of the editor.

One Comment

Comments are closed.

Really interesting! So progressive for her time! What a shame her history had been buried–yet someone was able to get your school named after her at one time. Mary