The rock legend and Pink Floyd co-founder shares everything from his musical origins to his opinions on the war in Ukraine, experiences of US government surveillance, and his ongoing ‘This Is Not A Drill’ tour.

POSTED IN THE CHRIS HEDGES REPORT September 30, 2022

Roger Waters, the British rock legend and co-founder of Pink Floyd, is in the midst of his “This Is Not A Drill” tour. In his concerts he weds his musical genius to the most pressing social issues of our day, including permanent war, police violence, the crimes of Israeli occupation against the Palestinians, the killing of the Palestinian journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, and the imprisonment of Julian Assange.

Waters has been an outspoken opponent of the NATO-fueled war in Ukraine, and a vocal supporter of contemporary social movements such as the Water Protectors at Standing Rock and global protests against police violence from the United States to Brazil and Britain. He joins The Chris Hedges Report for a wide-ranging conversation: from his youth and musical career to the political worldview that undergirds his provocative ‘This Is Not A Drill‘ tour.

Full transcript below.

Watch The Chris Hedges Report live YouTube premiere on The Real News Network every Friday at 12PM ET.

Listen to episode podcasts and find bonus content at The Chris Hedges Report Substack.

Studio: Adam Coley, Cameron Granadino, Dwayne Gladden

Post-Production: Dwayne Gladden

TRANSCRIPT

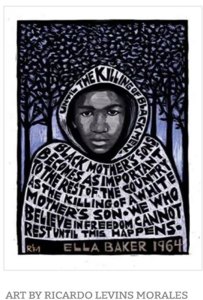

Chris Hedges: Roger Waters, the British rock legend and co-founder of Pink Floyd, is in the midst of his This Is Not a Drill tour. In his concerts, he weds his musical genius to the most pressing social issues of our day, including permanent war, police violence, the crimes of Israeli occupation against the Palestinians including the killing of the Palestinian journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, and the imprisonment of Julian Assange. When Waters performed the song “The Powers That Be”, above him on the enormous video screens are animated scenes of police brutality. The names of George Floyd, Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, and others flash overhead. Their crime is listed as “Being Black.” Their punishment is listed as “Death.”

Images from the Collateral Murder video, the Israeli bombing of Gaza, and numerous other police murders including those of the Syrian Ali al-Hamdan, killed by Turkish police; Rashan Charles, killed by British police; Matheus Mello Castro, shot by police in Brazil, provide the background to his music. Slogans of resistance pepper the performance. “F drones, F the Supreme Court, F Occupation. You can’t have occupation and human rights.” He dedicates a song to the water protectors at Standing Rock, and has a montage of US presidents from Ronald Reagan to Joe Biden, all correctly labeled as war criminals.

Waters returns us to the era when artists were not denuded of moral authority by commercial interests. He stands unequivocally with the oppressed. He stands unequivocally against the forces of oppression like Victor Jara, Mercedes Sosa, or Woody Guthrie of another era. He reminds us of who we must fight for, and who we must fight against.

Joining me to discuss his music and his tour, This Is Not a Drill tour, is Roger Waters. It’s a remarkable tour, and before we close, you can give us the upcoming dates. You have such longevity. I mean, you started Pink Floyd, and it’s kind of very poignant. You, in the concert, go back and talk about the co-founder of Pink Floyd, Syd. And the first concert I think you went to, in London, where you saw the Rolling Stones. But for me, you returned, in that concert, rock to its subversive origins. Was that your intent?

Roger Waters: No, it was not my intent. What was my intent? I don’t know. We were supposed to start this show in 2020, so we had prepared a show of sorts. Well, actually similar, with the similar intentions to expose the machinations of the powers that be and how murderous they are and so on and so forth. All the stuff that you see in the show. And then COVID hit, and we had to cancel in 2020. And we tried it again in ’21, and we had to cancel again. And blah, blah, blah. And we eventually got on the road in ’22.

In the meantime, I had written a couple of new songs, maybe three new songs during COVID, and one of them is fundamentally important. It’s called “The Bar”.

Chris Hedges: Yeah.

Roger Waters: I know you’ve seen a stick of the shows, so you’re aware of what it is. But “The Bar” is a very long song that I wrote sometime last year, in 2021. And it is based upon a concept that I developed that we all carry within us the potential to go to the bar, have a drink, and talk to people. Talk to our friends, meet and talk to our… But also talk to strangers, also talk to people who don’t agree with us about things. So the bar, for me, is a safe place, where we can express our opinions, but also demonstrate our love for one another, and our love for all our brothers and sisters all over the world, irrespective of their own ethnicity or religion or nationality. I know that sounds like a speech, what I’m saying, because it is a speech, it’s something that I say often. And I’m sure I say it at least once during the show.

So I sit at the piano and some of the band gather round, and in a very intimate atmosphere, I explained to the 16,000 people who were in the room that we are all sitting in the bar together. I’m getting quite emotional, Chris, even saying this to you now. Mind you, I was quite emotional just listening to your introduction, because it’s very moving to be noticed. And to have somebody as eloquent and as revered as you are to say those things about the show that I’m doing.

So, why am I talking about “The Bar”? Because it’s new. That’s new, in 2022, to what was already a show that was earnest and direct and very political. But what’s happened now, and why I’m so excited about doing this work now, is that by including bits – And we just do small bits of that song now – By including bits of that song now, it is an invitation to every single one of those 16,000 people to be in the bar. Not just with me, but with each other, and with everybody else who feels a kinship to the human race. A closer kinship to the human race than they do to profit, for instance. Or any one of any number of dogmas in different camps all around the world, where people are extreme and have been subverted, if you like, from their potential to be human and to love one another and look after one another.

Chris Hedges: But the concert is fierce against the forces of oppression. It had a kind of Orwellian quality to it. And when you take those kinds of stances, you make enemies.

Roger Waters: Yes, I do. And I often wonder how thick the dossier is in the FBI and the CIA, because I bet it’s quite thick. And I know from experience that occasionally – I’m talking about the USA now particularly, because I live in the USA, and so I have to have… I’m permanent, I’m sort of constantly reapplying for an O-1 visa, which is my permit to work, my permit to stay, to be resident in the United States.

And the last time I went to get it renewed was in the American Embassy in London a few years ago. Somebody else who was with me… I probably shouldn’t be telling you this, but, frankly, I couldn’t give a damn. And he’s a guy who works for me, and he’s worked for me for many years. So I have an O-1 visa, which is a visa they give to people who are unique in some way. Nobody can do what I do, because I’m me, and only I have my body of work. And it applies to actors and musicians, and all kinds of people.

And then people who work for people like me get O-2 visas, which are attached, if you like, to that. Well, we went in together, Chubba, my friend Chubba, who’s worked for me for 20 years. And I was 591, and he was 592 on the list. So suddenly, he got called in, 592. And they gave him his O-2 visa, and he was done. And I sat there for another two and a half hours even though I was the number before him. So I thought, oh my goodness, they’re in a room, having a meeting, trying to decide whether to let me back into the United States or not. And they did, and I’m happy that they did. But who knows, next time? It’s very difficult to know which way they’re going to jump.

And they must do the sums about, is this to our advantage, or not? And you have to believe that the neocons, the powers that be who run the United States and completely control all the politicians and the government. We know that’s just a charade. There’s really no difference between any of the politicians. Because, as we know, government can be purchased in the United States. That’s what Citizens United is, which is only about 10 years old, as far as I remember. But you can buy, purchase the election, which is weird that they would call themselves a democracy. And yet, government is for sale to the highest bidder.

So, what am I trying to say? I don’t know, I’ve sort of run off the rail slot.

Chris Hedges: Well, but it’s important. So I spoke in Florence, it was at the time a communist government. They invited me to speak to all graduating high school students, there were 10,000 of them in an auditorium. And when I came back to Newark, the same experience. I’m a US citizen with a valid US passport. They put me in a room for two hours, told me nothing, and then a supervisor came in to somebody behind the computer screen and said, he’s on a watch, tell him he can go. And I think that what they did to me is exactly what they did to you. It was intentional, just to let you know that they are watching you.

Roger Waters: Yeah, they are. I know that. I’ve been warned by people. I’ve been warned by people with connections. Oh, well it’s just that… Wouldn’t you rather be Martin Luther King than Malcolm X? If you get too extreme… And I had this conversation, I thought – This was in my own home, and I’m not going to mention the name of the guy who came and made this speech to me, but he’s an ex CIA desk. He ran the Middle Eastern desk for the CIA for a number of years. And there he was explaining to me that it’s probably much better to be moderate, that you have more impact and effect if you don’t get too Malcolm X-y.

And I thought to myself, well, they killed Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. And then at the end of it, the guy said to me – And it was quite chilling – He said, well, I just wouldn’t want to see anything happen to you. And I thought, fuck me, I’m being threatened in my own home by an ex CIA desk manager. Amazing. And I tried not to bat an eye, and I sort of didn’t, but I went, well, thank you for your time, man. But I do bear it in mind, sometimes. However, I don’t wander around looking over my shoulder.

Chris Hedges: Well, you didn’t pull any punches, I got to hand it to you. You did warn everyone at the beginning that if you’re one of those who likes Roger Water’s music but you don’t like his politics, you can F off to the bar. I guess, the bar being a place where maybe we can convert them.

Roger Waters: [inaudible].

Chris Hedges: And I thought, at the end of the concert, well, everybody was forewarned, completely forewarned. I’m going to wade into an area that is totally out of my expertise. But when you go back, and I want you to talk a little bit about, I found it very poignant when you were talking about your first dreams of creating this iconic group, Pink Floyd. And the very tragic life that finally took your co-founder, Syd. But that kind of political radicalism, wasn’t that more infused within rock and roll when you began in the ’60s? Or am I wrong about that?

Roger Waters: I don’t know if you’re right or wrong, because it’s not an area of interest, really.

Chris Hedges: Oh.

Roger Waters: Because the radicalism comes from my mother and my father, so it’s very… In fact, you and I may have even conversed about this briefly.

Chris Hedges: Yeah.

Roger Waters: Because I know that a lot of your… Not instincts, but a lot of your beliefs and things are attached to the memory of your father and the fact that he stood up so bravely for what he believed in when he was a minister and ran up against the church, and blah, and all of that.

So, I was chairman of the Young Socialists and the Youth Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in Cambridge when I was a 15-year-old. And that came, absolutely, from the fact that my mother was a card-carrying Communist up until 1956, which was the year when almost everyone in England stopped being a card-carrying Communist because the British Communist Party refused to condemn the invasion of Hungary, specifically, by the Russians. And so, that was a huge change that happened with the Communist part. But my childhood is kind of littered with Daily Worker bazaars, and political meetings in the front room.

My attachment to rock and roll was far less worthy. I couldn’t see how I could get enough money to buy a sports car and start pulling jigs, to use that parlance, unless I won the football pools or something like that. Because I couldn’t see how I could really make my way in the world in a way that I wanted. And rock and roll was sort of the only thing. And it was like winning the lottery or the football pools, because it’s so unlikely that you would ever make a shilling out of a garage band. They weren’t called garage bands there, but by putting a pop group together.

But by some weird quirk of fate, it happened to me, partly because of Syd’s great talent earlier on, because he was a writer of some note. I can still remember some of his lyrical work from those days. And not just his lyrics, as well. He was something of a visionary in terms of his musical applications, as well, though he learned a lot from Love, and one or two of the other West Coast American groups.

There was precious little going on in England at the time. The music industry, by and large, was run by a lovely man who was called Parnes, Larry Parnes. And he was a manager, and he was also a publisher, I think. And in the trade he was known as Larry Parnes, Shillings and Pence, which was a nice tip of the hat to his attachment to the bottom line. And so, rock and roll was full of people called Vince Eager and Marty Wild. All these names were invented for them by Larry Parnes, Shillings and Pence, as a way of selling their wares that were written by other people. They never wrote anything. They were the figureheads.

So Tin Pan Alley was sort of owned and run by the Larry Parnes, Shillings and Pences of this world. And they would pluck people with greasy hair and nice quiffs and a reasonable voice from somewhere or other. God knows where they found them. And they were the pop stars of the time. And that’s why the Beatles are important, I think, because that only changed when the Beatles and others, having latched onto Woody Guthrie, who you mentioned before, and others. And Pete Seeger, and a bit of American folk, started to understand that they maybe could be singing about things that were relevant in their lives.

In the Beatles’s case, it was like “Eleanor Rigby”, or “She’s Leaving Home”, or kitchen sink drama about the reality of their lives. Others, mainly more in America, attached to sleeping in railway cars. And the Woody Guthrie end of rock and roll, which was in itself attached very much to Huey Ledbetter and Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday and the American tradition. But somehow some of that filtered through to us young people in England, probably via a crystal set. American Forces Network overseas, and Radio Luxembourg, and all that. That was the subversive bit of it, it was the beginnings of radio. For me, anyway. That was what [inaudible]…

Chris Hedges: Although, it wasn’t just the music. The reason I mentioned Victor Jara, Mercedes Sosa, and Woody Guthrie is because they used their artistic talent, as I think you do, as a frontal assault. I mean, Victor Jara was murdered. Mercedes Sosa was exiled. Woody Guthrie was all but internally exiled.

And this is what so impressed me about it, you just didn’t pull any punches at all. I mean, that’s what made it, I think, so powerful. And I just want to say that it also had artistic integrity. It wasn’t a polemic. It could have been a polemic, in which case it would’ve fallen flat

Roger Waters: Yeah. Well, it’s a disguised polemic.

Chris Hedges: [laughs] Well, that’s what all great art is.

Roger Waters: Yeah. Well, okay. Yeah. I believe you to be right. You’re exactly right. I could name English artists who are very, very earnest and convinced, and really laudable because of what they do. I can’t not mention Billy Bragg, who’s a name from the English past of the thing. But it’s so earnest and so direct that it’s no longer poetic or really very interesting, in a way. So it’s to circumvent that. But to circumvent it is not a subterfuge, it’s not an intellectual process. Syd could do it. Not that he was political, he wasn’t, but he could do it and introduce ideas into his own, because his work was rooted in the work of Hilaire Belloc and other English romantics in a way that was really interesting and laudable.

But my circumvention of it only has to do with the fact that, even talking to you now, I’m capable of welling up and becoming overcome emotionally. By not my situation, really, but the situation that I see my brothers and sisters in. And I cannot not respond to it. But… Sorry.

Chris Hedges: I want to talk about war. Your father was killed in World War II.

Roger Waters: Yeah.

Chris Hedges: You wrote one of the greatest, I think, modern anti-war anthems ever written, “Us and Them”. And…

Roger Waters: It’s Rick Wright. It’s Rick Wright’s music, actually.

Chris Hedges: Is it? Okay. But it’s an unbelievable song.

But I want to talk about war, because it had a personal effect on you. And I love your understanding and hatred of war and violence. Which, again, I think came through in your concert.

Roger Waters: Well, I spent this morning over this computer writing the second bit of a letter to Olena Zelenska.

Chris Hedges: I read your first one. It was great.

Roger Waters: All right. So, read the first one. She replied with a very short Twitter just telling me, you’re wrong. The Russians have to give up. The Russians have to give up, and then the war will be over.

So I’ve written another one to her, which I wrote some of this morning, trying to explain to her that they both have to give up. Clearly, there’s no good end to this war.

There has to be a ceasefire, and then there have to be diplomatic negotiations. And in the letter I’ve written all this stuff about how weird is it, that all the propaganda is going on, the waving of the blue and yellow flags, and the pouring of arms and weapons into the Ukraine at the cost, obviously, mainly of young Ukrainian men and women who are being slaughtered because they’re cannon fodder. And certainly, the United States government couldn’t care less about them and is totally disinterested in Ukraine. All it wants is to further its geopolitical ends. And we know this, but those of us who care about people think, oh my God, this is horrific. How can we stop this war?

Well, obviously, you have to talk to Vladimir Putin, who is the new Hitler. You can’t even talk to him. But what’s different? And we’re heading towards Ukraine being the new Cuba. We’re having another Cuban missile crisis right now in Eastern Europe like we had in 1962. But two things were different in… Well, we don’t know. One thing was certainly different. And what was that? John Fitzgerald Kennedy was speaking to Nikita Khrushchev on the telephone. We know this because William Polk was in the room. And so was Ray McGovern, and they’ve told us what was going on during those moments. When the hawks were saying, press the button, press the button, let’s kill them before they kill us. And to his eternal credit, JFK went, whoa, hold on.

And he listened to wiser voices, and he spoke to Khrushchev, and they figured it out. And Khrushchev figured it out, as well. And he went, all right, I understand. Is Biden talking to Putin? Of course he’s not. Biden is sitting there saying, you are Hitler, and we’re going to remove you from power. Hang on a minute. It’s not your country, Joe. You doddering old fool. It’s Russia. It’s their country. It’s nothing to do with you. What? This is insane.

You can’t try and manufacture regime change in one of the most powerful nuclear armed countries in the… Russia? Did you not watch the Second World War, Joe, when you were a little kid? Did you not see 23 million of them died fighting the Nazis, saving you and me from the tyranny of the Third Reich? The Russians did that. You think they’re going to take any notice of you telling them that they’ve got to get a new leader? You are uniting the Russian people behind Vladimir Putin. What you think of him is irrelevant.

And it’s crazy. You can’t have the president of a great, great country like the United States poking another world leader in the eye with a bloody sharp stick. It’s insane that they’ve allowed foreign policy. I read John Pilger’s piece last week, where he talks about… Oh, Christ. Harold Pinter, talking about American foreign policy.

Chris Hedges: Yeah, this is in his Nobel Prize speech.

Roger Waters: Exactly.

Chris Hedges: Brilliant, brilliant.

Roger Waters: What does he say? He says, American foreign policy is like a bully in the school yard. You say, you do as we say or we’re going to kick your teeth in. That’s American foreign policy. What? How crude and debilitating and disgusting and old fashioned. What, are you living in the ninth century? What is wrong with you? What’s wrong with them, of course, is that they picked up from Irving Kristol and those early neocons, and something of the New American Century, that they could be the unipolar power and that they can rule the world.

Chris Hedges: Well, you know we’re all in…

Roger Waters: Nobody’s explained to them….

Chris Hedges: …We’re all in trouble when Henry Kissinger is the voice of reason, which he is. And you got in a lot of trouble on CNN, I don’t know if I watched the whole thing. But you were not saying anything different than Kissinger had said, which is that they should give land for peace. The war has to end. Because whatever you think about Kissinger, and of course I think he’s a war criminal along with all those presidents you listed at your concert, he certainly understands geopolitics. And he understands the danger, and as I think you just laid out, of the Ukraine policy.

Roger Waters: Yeah. So that’s what we do all day. You do it, as well. This is what we do. We the people who represent the we the people, who somewhere understand that we have to figure out a method of collaborating with one another that might, at the end of the day, save this beautiful planet that we all call home. Because they, the powers that be, the neocons, the profit mongers, the war machine, are working as hard as they can to destroy it as fast as they can. Including, possibly, with nuclear war.

And one… Am I loath to go into this arena? Probably. The Evangelical Christian right… I’m sure it’s a worry to you, as well. The idea of the rapture and how attractive that is…

Chris Hedges: Yeah.

Roger Waters: …To some people, is deeply, deeply distressing, obviously, to anybody who’s even thinking about the questions that we’re talking about now. Because they push us all in the…

Chris Hedges: Well, it’s a kind of yearning for apocalyptic violence. You look at the End Time series, and I wrote a book on it: American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America.

Roger Waters: I read it.

Chris Hedges: I was trying to reach out to them.

I want to go back, I have to ask you this. I’ve always wanted to ask a great musician and a great writer this. So, those of us who write look at language as a form of music and having a rhythm, if you’re a good writer. And you’re a great writer. But you wed your lyrics to music, which I, of course, am incapable of doing. And I’m wondering how that’s different from just writing?

Roger Waters: Here’s a poem that I wrote when I first read Cormack McCarthy’s great novel, All the Pretty Horses. I’ve read all his novels, many times. But that particular… There is a magic in some books that sucks a man into connections with the spirits, hard to touch, that join him to his kind. A man will eke the reading out, guarded like a canteen in the desert heat, but sometimes needs must drink. And then, the final drop falls sweet. The last page turns, the end.

It’s a very short poem about everybody who loves prose or poetry. But prose, I’m really talking about. There’s that last 10 pages of a book where you keep putting it down on the bedside table, because you do not want it to end.

Chris Hedges: Yeah.

Roger Waters: Because it’s so musical. It’s a bit like A River Runs Through It. Those last two pages, it’s normally…

Chris Hedges: The last paragraph of A River Runs Through It, and the last paragraph of The Dead, by James Joyce.

Roger Waters: Exactly.

Chris Hedges: But you go to another level. So you’re a writer, obviously a very gifted writer. But that writing doesn’t stand alone, it becomes fused with music. And that’s a mystery to me, that process.

Roger Waters: Well I’m happy to say that it does stand alone now, because I’ve written a memoir. And it’s great. I love it. And it’s another COVID thing, because before COVID, I had no idea that I could write prose.

Chris Hedges: Oh, really? [laughs]

Roger Waters: Yes, that’s only… Yeah.

Chris Hedges: That’s funny.

Roger Waters: I knew I could write songs a bit, but prose. And I sat down one day and wrote like 10,000 words or something and thought, wow, I can do this. This is cool. And it is, it’s one of the great joys of my life now, is that I love to write.

Chris Hedges: Well Patti Smith just did that with Just Kids. A beautiful book.

Roger Waters: Yes, she did. Yeah.

Chris Hedges: Beautiful book.

Roger Waters: Yeah, it was beautiful.

Chris Hedges: But I want to go back to that. When you write, the words are not standing alone when you’re writing lyrics. What’s the mental process of wedding those words to music? Do they play off of each other? Do you write to the music? How does it work?

Roger Waters: It’s different. So I either work with a guitar or with a piano. At the piano, though I hardly play the piano. In fact, these shows are the first time I’ve ever played piano, actually.

Chris Hedges: Because “The Bar” I think you’re playing the piano. Right? Yeah.

Roger Waters: Yeah. I’m playing the piano in “The Bar”. So with “The Bar”, for instance, I think I was just fiddling around in B flat. B flat. And B flat, and an F, and probably just the faintest glimmer of an idea. Probably the first line. “Does everybody in the bar feel pain? Lord knows I do.”

No, that’s the second voice, or the third verse. “Yeah, sure they do. I guess we all feel pretty much the same, kind of wore out by this crazy fucking zoo.” What is it? “We sold the family farm for a snake oil, bought into the carpetbaggers’ lies.” And now I’m right into the beginning of the 20th century in North America with the robber barons and that bullshit that they sold, all the settler colonialists in the country. They sold them the idea that this was perfect. And it sort of was. They had slaves, so they could make fortunes without doing any work. And then they decided to murder all the Indigenous people, and it was lovely. And just steal everything and spend it on themselves. And it’s great. It’s a brilliant idea if you don’t have to internalize the terrible damage that you do yourself when you commit genocide on another people.

Israelis are suffering it now. Although most of them don’t seem to know it, but there they are committing genocide on the Palestinian people. Or trying to, as best as they can. And they must be paying a price that we can’t possibly imagine.

Chris Hedges: No, I lived in Israel. You’re very right. Yeah, it’s very corrosive. And I think the militarization of Israeli society mirrors the militarization of American society, and it’s exactly the same poison. I find many parallels. We’re just going to stop for a minute. Before we stop, though, tell us your next tour dates, so people can go. What’s coming up?

Roger Waters: If I could tell you that, I would. I

Chris Hedges: So tell us your website, where they can get it. Oh, I just want to ask, before we close, I found that very moving. This Is Not a Drill, was a response to loss, to… I think it’s Syd’s death, right?

Roger Waters: Yeah, yeah. When we lose someone that we really love, it serves to remind us that this is not a drill. Somebody else, a friend of mine who died, Donald Hall, who was a [inaudible]…

Chris Hedges: Oh, great poet. Great poet.

Roger Waters: Yeah. And I became a friend of his very late in his life, and we only knew each other for like the last two years of his life. But I was very close to Donald, and we used to talk and talk. And what was I trying to say?

Chris Hedges: About loss.

Roger Waters: Yeah. After he died, I wrote his assistant, who’s called Kendall, a letter. And I think in it, I said, we only get one chance. That’s what I mean by this is not… We get one chance. So it behooves us, if we have the opportunity, to walk the path that we choose with grace and love and whatever, I can’t remember exactly the words that I… Which Donald Hall did. And so, if we are lucky enough to figure out that that is what brings joy to our life, is to walk the path with grace. We are lucky men and women who discover that early enough, and discover that getting another phone or car or being a billionaire is not going to buy… You can’t buy joy.

Chris Hedges: No.

Roger Waters: But I said to Kendall, Donald Hall walked the part of his life with such grace and courage. And because Jane, his wife, Jane Kenyon, is quite…

Chris Hedges: Also a great poet, by the way.

Roger Waters: Also a great poet. Yeah. Died tragically. And Donald Hall and I shared a journey together, which is part of what brought us together. Because he wrote a book called Essays After 80. And one of the books was called, There is Only One Road. And it was about him and his first wife, whose name I will remember in a minute. It begins with K as well. But it doesn’t matter.

They went in a Morris Minor to Athens in, well, it was just before I went. 1959, I think, something like that. So they left Vienna and drove down through Yugoslavia and whatever. And when they were going through Yugoslavia, they stopped, and there was a bloke by the road who miraculously spoke English. And they said, is this the road to Zagreb? And he looked at them, slightly pityingly, there is only one road, in Yugoslavia. Which is great, and that was something to say. And then he talks about the rest of their journey, and they go and play… Kirby? Is she called Kirby? It doesn’t matter.

Anyway, 20 years later when they’ve split up and the marriage is over and been over, she gets cancer. And Donald goes and lives with her for the six months it takes her to die. All right? Which is very moving in a kind of different way. But at the end of his story, he comes back to the beginning. And she’s died. Kirby, her name is Kirby. And he says, there is only one road.

Chris Hedges: All right, we’re going to stop there. This Is Not a Drill. I want to thank The Real News Network, its production team: Cameron Granadino, Adam Coley, Dwayne Gladden, and Kayla Rivera. You can find me at chrishedges.substack.com.

Image by One More Time