Andrea Jenkins on racism as a public health crisis: “George Floyd would still be breathing right now if it weren’t for racism.”

“It’s the same map,” she said.

All of those health issues are rooted in Minneapolis’ history of racist housing covenants and redlining that pushed Black residents and other communities of color into concentrated pockets of the city.

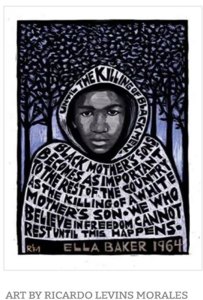

Now, in the wake of George Floyd’s death and with the coronavirus pandemic disproportionately impacting people of color, Minneapolis and Hennepin County have officially voted to declare racism a public health emergency.

“I think it’s an important statement in these times,” Musicant said. “My hope is that it’s more than that as well.”

Nationwide studies have connected racism to inequitable health outcomes for diseases including cancer, diabetes, hypertension and coronary heart disease, according to the city’s declaration.

In Minneapolis, Black and Indigenous infants die at rates three to four times higher than white infants, according to a 2018 report by the health department. The city’s residents are more likely to be hospitalized for asthma if they live in zip codes with more than 50% residents of color and with more than 40% of residents below the poverty line, according to a separate 2018 report. Hennepin County’s Black residents, only 12% of the population, made up 43% of residents diagnosed with HIV in 2016. Native Americans in the county are dying of opioids at a rate 10 times higher than the average resident.

Public health officials have tied race to health for several years, but the push for governments to declare racism as a pressing public health issue began in 2019 in the cities and counties around Pittsburgh and Milwaukee. Since Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer on Memorial Day, several other cities, counties and some entire states, including Wisconsin and Michigan, have followed suit.

Dr. Michele Allen, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota Medical School and director of the Health Disparities Research Program, said she sees the impacts of racism in the structural determinants of health. Long-standing social and economic inequities make it so Black, Latino and other populations of color have less access to health care and are more likely to have to make tough decisions about spending for health care.

Not only does race factor into the level of access Americans have to health care, it also impacts the way people are treated when they do see a physician. There is an “irrefutable” amount of data documenting that doctors treat people differently based on race, Allen said.

COVID-19 “really highlights the intersection of social determinants and historical health issues that make people more vulnerable,” Allen said.

Black and Latino people are more likely to work the jobs deemed “essential” that require close proximity with others, and they are more likely to live in housing where it’s more difficult to socially distance, she said. Historical factors like lack of quality food access in many communities of color have led to higher rates of the underlying conditions that exacerbate COVID-19, like diabetes and obesity.

“George Floyd would still be breathing right now if it weren’t for racism,” Council Vice President Andrea Jenkins (Ward 8) said.

Systemic racism has been a defining characteristic of the United States before the nation even existed, Jenkins said, and if people aren’t working against it, they can become complicit. Built-in inequalities must be fought against, she said, and naming racism as a public health crisis begins to address some of those underlying issues found in America’s criminal justice, education and housing systems.

The resolution approved by the Minneapolis City Council calls on the body to recognize “the severe impact of racism on the well-being of residents and the city overall” and to commit funding and staff to work to repair harm done to impacted communities. It calls for investments in housing, community infrastructure and small-business development for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). It also calls for creating a sustainable source for funding for youth development programming, an area in which Musicant said has seen a decline in investment since the early 2000s.

Hennepin County’s resolution directs the entity to advocate policies to improve health outcomes for BIPOC residents and gives county staff three months to create a timeline to improve service delivery for people of color and to assess internal policies to improve health outcomes in those communities.

“Ultimately this resolution is about the health and well-being of Hennepin County residents who have borne the brunt of racial discrimination and racial inequity through various different systems,” Commissioner Angela Conley (District 4) said.

Allen said the combination of COVID-19 and the death of George Floyd has created a unique opportunity to raise awareness about these discrepancies and have more white people receptive to and exhibiting understanding of the concept. Naming racism as a public health emergency raises the issue to a level at which people think about acute responses and look for long-term solutions, Allen says. She hopes it will keep the issue off the back burner.

By making racism a public health issue, more data can be brought in to identify and try to address the longstanding inequities in our society, Musicant said. The resolution reminds her of when the city declared violence a public health crisis in the mid-2000s, and she believes it will give the city an opportunity to look at a wide array of factors.

Minneapolis last completed a report on racial disparities in 2018. Musicant is hopeful that new data from the 2020 census will help update the health department’s understanding of where those discrepancies are most felt today.

Jenkins is glad that the county has also made the declaration but said it is critical for the state to get involved as well, because the issue doesn’t end at city or county lines. The Minnesota House passed a resolution naming racism as a public health crisis statewide, but it ultimately failed in the Senate. Only Olmsted County has joined Minneapolis and Hennepin County in making such a declaration in Minnesota.

“We have to be coordinated in this,” Jenkins said.

DONATE AND SUBSCRIBE TO RISE UP TIMES

Truth is not fake news.

Justice is not fake news.

Rise Up Times needs your help to bring you timely articles and information about so many important current issues in these Rise Up Times. Subscribe to RiseUpTimes.org Support independent media. Please donate today and share articles widely.