Forget About Siri and Alexa — When It Comes to Voice Identification, the “NSA Reigns Supreme”

The technology works by analyzing the physical and behavioral features that make each person’s voice distinctive, such as the pitch, shape of the mouth, and length of the larynx. An algorithm then creates a dynamic computer model of the individual’s vocal characteristics.

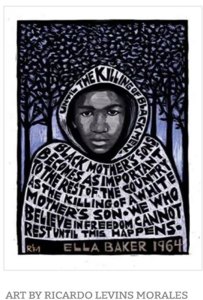

Illustration: Brandon Blommaert for The Intercept

Illustration: Brandon Blommaert for The Intercept

It wasn’t until 1985 that the FBI, thanks to intelligence provided by a Russian defector, was able to establish the caller as Ronald Pelton, a former analyst at the National Security Agency. The next year, Pelton was convicted of espionage.

Today, FBI and NSA agents would have identified Pelton within seconds of his first call to the Soviets. A classified NSA memo from January 2006 describes NSA analysts using a “technology that identifies people by the sound of their voices” to successfully match old audio files of Pelton to one another. “Had such technologies been available twenty years ago,” the memo stated, “early detection and apprehension could have been possible, reducing the considerable damage Pelton did to national security.”

These and other classified documents provided by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden reveal that the NSA has developed technology not just to record and transcribe private conversations but to automatically identify the speakers.

Media for the people! Learn more about Rise Up Times and how to sustain

People Supported News.

Follow RiseUpTimes on Twitter RiseUpTimes @touchpeace

Americans most regularly encounter this technology, known as speaker recognition, or speaker identification, when they wake up Amazon’s Alexa or call their bank. But a decade before voice commands like “Hello Siri” and “OK Google” became common household phrases, the NSA was using speaker recognition to monitor terrorists, politicians, drug lords, spies, and even agency employees.

The technology works by analyzing the physical and behavioral features that make each person’s voice distinctive, such as the pitch, shape of the mouth, and length of the larynx. An algorithm then creates a dynamic computer model of the individual’s vocal characteristics. This is what’s popularly referred to as a “voiceprint.” The entire process — capturing a few spoken words, turning those words into a voiceprint, and comparing that representation to other “voiceprints” already stored in the database — can happen almost instantaneously. Although the NSA is known to rely on finger and face prints to identify targets, voiceprints, according to a 2008 agency document, are “where NSA reigns supreme.”

It’s not difficult to see why. By intercepting and recording millions of overseas telephone conversations, video teleconferences, and internet calls — in addition to capturing, with or without warrants, the domestic conversations of Americans — the NSA has built an unrivaled collection of distinct voices. Documents from the Snowden archive reveal that analysts fed some of these recordings to speaker recognition algorithms that could connect individuals to their past utterances, even when they had used unknown phone numbers, secret code words, or multiple languages.

As early as Operation Iraqi Freedom, analysts were using speaker recognition to verify that audio which “appeared to be of deposed leader Saddam Hussein was indeed his, contrary to prevalent beliefs.” Memos further show that NSA analysts created voiceprints for Osama bin Laden, whose voice was “unmistakable and remarkably consistent across several transmissions;” for Ayman al-Zawahri, Al Qaeda’s current leader; and for Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, then the group’s third in command. They used Zarqawi’s voiceprint to identify him as the speaker in audio files posted online.

The classified documents, dating from 2004 to 2012, show the NSA refining increasingly sophisticated iterations of its speaker recognition technology. They confirm the uses of speaker recognition in counterterrorism operations and overseas drug busts. And they suggest that the agency planned to deploy the technology not just to retroactively identify spies like Pelton but to prevent whistleblowers like Snowden.

Always Listening

CIVIL LIBERTIES EXPERTS are worried that these and other expanding uses of speaker recognition imperil the right to privacy. “This creates a new intelligence capability and a new capability for abuse,” explained Timothy Edgar, a former White House adviser to the Director of National Intelligence. “Our voice is traveling across all sorts of communication channels where we’re not there. In an age of mass surveillance, this kind of capability has profound implications for all of our privacy.”

Edgar and other experts pointed to the relatively stable nature of the human voice, which is far more difficult to change or disguise than a name, address, password, phone number, or PIN. This makes it “far easier” to track people, according to Jamie Williams, an attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “As soon as you can identify someone’s voice,” she said, “you can immediately find them whenever they’re having a conversation, assuming you are recording or listening to it.”

The voice is a unique and readily accessible biometric: Unlike DNA, it can be collected passively and from a great distance, without a subject’s knowledge or consent. Accuracy varies considerably depending on how closely the conditions of the collected voice match those of previous recordings. But in controlled settings — with low background noise, a familiar acoustic environment, and good signal quality — the technology can use a few spoken sentences to precisely match individuals. And the more samples of a given voice that are fed into the computer’s model, the stronger and more “mature” that model becomes.

In commercial settings, speaker recognition is most popularly associated with screening fraud at call centers, talking to voice assistants like Siri, and verifying passwords for personal banking. And its uses are growing. According to Tractica, a market research firm, revenue from the voice biometrics industry is poised to reach nearly $5 billion a year by 2024, with applications expanding to border checkpoints, health care, credit card payments, and wearable devices.

A major concern of civil libertarians is the potential to chill speech. Trevor Timm, executive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, noted how the NSA’s speaker recognition technology could hypothetically be used to track journalists, unmask sources, and discourage anonymous tips. While people handling sensitive materials know they should encrypt their phone calls, Timm pointed to the many avenues — from televisions to headphones to internet-enabled devices — through which voices might be surreptitiously recorded. “There are microphones all around us all the time. We all carry around a microphone 24 hours a day, in the form of our cellphones,” Timm said. “And we know that there are ways for the government to hack into phones and computers to turn those devices on.”

“Despite the many [legislative] changes that have happened since the Snowden revelations,” he continued, “the American people only have a partial understanding of the tools the government can use to conduct surveillance on millions of people worldwide. It’s important that this type of information be debated in the public sphere.” But debate is difficult, he noted, if the public lacks a meaningful sense of the technology’s uses — let alone its existence.

A former defense intelligence official, who spoke to The Intercept on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss classified material, believes the technology’s low profile is not an accident. “The government avoids discussing this technology because it raises serious questions they would prefer not to answer,” the official said. “This is a critical piece of what has happened to us and our rights since 9/11.” For the technology to work, the official noted, “you don’t need to do anything else but open your mouth.”

These advocates fear that without any public discussion or oversight of the government’s secret collection of our speech patterns, we may be entering a world in which more and more voices fall silent.

The U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) building is seen October 9, 2012 in Boulder, Colorado. Photo: Dana Romanoff/Getty Images

The New Voice Tools

WHILE AMERICANS have been aware since 2013 of the NSA’s bulk collection of domestic and overseas phone data, the process by which that raw data is converted into meaningful intelligence has remained largely classified. In 2015, The Intercept reported that the NSA had built a suite of “human language technologies” to make sense of the extraordinary amount of audio the government was collecting. By developing programs to automatically translate speech into text — what analysts called “Google for voice” — the agency could use keywords and “selectors” to search, read, and index recordings that would have otherwise required an infinite number of human listeners to listen to them.

Speaker recognition emerged alongside these speech-to-text programs as an additional technique to help analysts sort through the countless hours of intercepts streaming in from war zones. Much of its growth and reliability can be traced to the NSA and Department of Defense’s investments. Before the digital era, speaker recognition was primarily practiced as a forensic science. During World War II, human analysts compared visual printouts of vocal frequencies from the radio. According to Harry Hollien, author of “Forensic Voice Identification,” these “visible speech” machines, known as spectrograms, were even used to disprove a rumor that Adolf Hitler had been assassinated and replaced by a double.

“Voiceprints were something you could look at,” explained James Wayman, a leading voice recognition expert who chairs federal efforts to recommend standards for forensic speaker recognition. He pointed out that the term “voiceprint,” though widely used by commercial vendors, can be misleading, since it implies that the information captured is physical, rather than behavioral. “What you have now is an equation built into a software program that spits out numbers,” he said.

Those equations have evolved from simple averages to dynamic algorithmic models. Since 1996, the NSA has funded the National Institute of Standards and Technology Speech Group to cultivate and test what it calls the “most dominant and promising algorithmic approach to the problems facing speaker recognition.” Participants testing their systems with NIST include leading biometric companies and academics, some of whom receive funding from the NSA and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA.

The NSA’s silence around its speaker recognition program makes it difficult to determine its current powers. But given the close ties between NSA-funded academic research and private corporations, a good approximation of the NSA’s capabilities can be gleaned from what other countries are doing — and what vendors are selling them.

For instance, Nuance, an industry leader, advertises to governments, military, and intelligence services “a country-wide voice biometric system, capable of rapidly and accurately identifying and segmenting individuals within systems comprising millions of voiceprints.” In 2014, the Associated Press reported that Nuance’s technology had been used by Turkey’s largest mobile phone company to collect voice data from approximately 10 million customers.

In October, Human Rights Watch reported that the Chinese government has been building a national database of voiceprints so that it could automatically identify people talking on the phone. The government is aiming to link the voice biometrics of tens of thousands of people to their identity number, ethnicity, and home address. According to HRW, the vendor that manufactures China’s voice software has even patented a system to pinpoint audio files for “monitoring public opinion.”

In November, a major international speaker recognition effort funded by the European Union passed its final test, according to an Interpol press release. More than 100 intelligence analysts, researchers, and law enforcement agents from over 50 countries — among them, Interpol, the U.K.’s Metropolitan Police Service, and the Portuguese Polícia Judiciária — attended the demonstration, in which researchers proved that their program could identify “unknown speakers talking in different languages … through social media or lawfully intercepted audios.”

NSA documents reviewed by The Intercept outline the contours of a similarly expansive system — one that, in the years following 9/11, grew to allow “language analysts to sift through hundreds of hours of voice cuts in a matter of seconds and selects items of potential interest based on keywords or speaker voice recognition.”

“Dramatic” Results

A PARTIAL HISTORY of the NSA’s development of speaker recognition technology can be reconstructed from nearly a decade’s worth of internal newsletters from the Signals Intelligence Directorate, or SID. By turns boastful and terse, the SIDtoday memos detail the transformation of voice recognition from a shaky forensic science conducted by human examiners into an automated algorithmic program drawing on massive troves of voice data. In particular, the memos highlight the ways in which U.S. analysts worked closely alongside British counterparts at the Government Communications Headquarters, or GCHQ, to process bulk voice recordings from counterterrorism efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan. GCHQ, which declined to answer detailed questions for this article, praised its systems in internal newsletters for “playing an important part in our relationship with NSA.”

While it can occasionally be difficult to distinguish between SIDtoday’s anticipatory announcements and the technology’s actual capabilities, it’s clear that the NSA has been using automated speaker recognition technology to locate and label “voice messages where a speaker of interest is talking” since at least 2003. Anytime a voice was intercepted, a SIDtoday memo explains, voice recognition technology could model and compare it to others in order to answer the question: “Is that the terrorist we’ve been following? Is that Usama bin Laden?”

But the NSA’s system did far more than answer yes-or-no questions. In a series of newsletters from 2006 that spotlight a program called Voice in Real Time, or Voice RT, the agency describes its ability to automatically identify not just the speaker in a voice intercept, but also their language, gender, and dialect. Analysts could sort intercepts by these categories, search them for keywords in real time, and set up automatic alerts to notify them when incoming intercepts met certain flagged criteria. An NSA PowerPoint further confirms that the Voice RT program turned its “ingestion” of Iraqi voice data into voiceprints.

The NSA memos provided by Snowden do not indicate how widely Voice RT was deployed at the time, but minutes from the GCHQ’s Voice/Fax User Group do. Notes from British agents provide a detailed account of how the NSA’s speaker recognition program was deployed against foreign targets. When its Voice/Fax User Group met with NSA agents in the fall of 2007, members described seeing an active Voice RT system providing NSA’s linguists and analysts with speaker and language identification, speech-to-text transcription, and phonetic search abilities. “Essentially,” the minutes say of Voice RT, “it’s a one stop shop. … [A] massive effort has been extended to improve deployability of the system.” By 2010, the NSA’s Voice RT program could process recordings in more than 25 foreign languages. And it did: In Afghanistan, the NSA paired voice analytics with mapping software to locate cell-tower clusters where Arabic was spoken — a technique that appeared to lead them to discover new Al Qaeda training camps.

The GCHQ, for its part, used a program called Broad Oak, among others, to identify targets based on their voices. The U.K. government set up speaker recognition systems in the Middle East against Saudi, Pakistani, Georgian, and Iraqi leaders, among others. “Seriously though,” GCHQ minutes advise, “if you believe we can help you with identifying your target of interest amongst the deluge of traffic that you have to wade through, feel free to approach us and we will happily discuss your requirements and hopefully offer a swift and accurate solution.”

It was not an empty offer. Minutes from 2009 boast of GCHQ agents outperforming their NSA counterparts when targeting Adil Abdul Mahdi, one of the vice presidents of Iraq at the time. “Since we have been consistently reporting on him [the vice president] faster than they, NSA have dropped their involvement. … This good performance has enhanced our reputation at NSA.” And a 2010 GCHQ research summary shows both agencies collaborating to conduct joint experiments with their voice analytics programs.

But the development of speaker recognition tools was not always seamless. In its early stages, the technology was nowhere near as powerful or effective as it is today. The former defense intelligence official recalls that while analysts were able to play voice samples at their workstations, searching for an important sample was a challenge, since the audio was not indexed. In a 2006 letter to the editor published in SIDtoday, one analyst complains of the introduction of the voice tools being “plagued by crashes” and compares their initial speed to “molasses in January in Juneau.”

By the next year, however, it was clear that speaker recognition had significantly matured. A memo celebrating the NSA’s special collection for then-Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s New York City trip for the United Nations General Assembly provides a detailed study of the technology in action. After obtaining legal authorization, analysts configured a special system to target the phones of as many of the 143 Iranian delegates as possible. On all of this incoming traffic, they ran speech activity detection algorithms to avoid having analysts listen to dead air; keyword searches to uncover “the passing of email addresses and discussion of prominent individuals;” and speaker recognition to successfully locate the conversations of “people of significant interest, including the Iranian foreign minister.”

In an announcement for a new NSA audio-forensics lab that opened in Georgia that year, the agency notes plans to make these speech technologies available to more analysts across the agency. And a SIDtoday memo from the following year reported system upgrades that would allow analysts to “find new voice cuts for a target that match the target’s past recordings.”

When targets developed strategies to evade speaker recognition technologies, the tools evolved in response. In 2007, analysts noticedthat the frequencies of the intercepts of two targets they had identified as Al Qaeda associates were out of normal human ranges. Over the next several years, analysts picked up on other targets modulating their voices in Yemen, Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere, “most likely to avoid identification by intelligence agencies.” Some of the audio cuts they observed twisted the speaker’s vocal pitches so that they sounded like “a character from Alvin and the Chipmunks.” This led analysts to speculate that AQAP members involved in the December 2009 bombing attempt in Detroit had escaped government recognition by masking their voices on new phone numbers.

By 2010, agency technologists had developed a solution for “unmasking” these modulated voices. Called HLT Lite, the new software searched through recordings for modified or anomalous voices. According to SIDtoday, the program found at least 80 examples of modified voice in Yemen after scanning over 1 million pieces of audio. This reportedly led agents to uncover persons of interest speaking on several new phone numbers.

As these systems’ technical capabilities expanded, so too did their purview. A newsletter from September 2010 details “dramatic” results from an upgraded voice identification system in Mexico City — improvements that the site’s chief compared to “a cadre of extra scanners.” Analysts were able to isolate and detect a conversation pertaining to a bomb threat by searching across audio intercepts for the word “bomba.”

Voice recognition systems could also be readily reconfigured for uses beyond their original functions. GCHQ minutes from October 2008 describe how a system set up for “a network of high level individuals involved with the Afghan narcotics trade” was later “put to imaginative use.” To identify further targets, analysts ran the system “against a whole zip code that brings in a large amount of traffic.”

Network equipment in a server room. Photo: Vladimir Trefilov/Sputnik/AP

Network equipment in a server room. Photo: Vladimir Trefilov/Sputnik/AP

From the Battlefield to the Agency

THE NSA SOON realized that its ability to process voice recordings could be used to identify employees within the NSA itself. As the January 2006 memo that discussed Ronald Pelton’s audio explained, “Voice matching technologies are being applied to the emerging Insider Threat initiative, an attempt to catch the ‘spy among us.’”

The Insider Threat initiative, which closely monitors the lives of government employees, was publicly launched by the Obama administration, following the leaks of U.S. Army whistleblower Chelsea Manning. But this document seems to indicate that the initiative was well under way before Obama’s 2011 executive order.

It’s not surprising that the NSA might turn the same biometric technologies used to detect external threats onto dissenters within its ranks, according to Freedom of the Press Foundation’s Trevor Timm. “We’ve seen example after example in the last 15 years of law enforcement taking invasive anti-terror tools — whether it’s location tracking or face recognition or this technology used to identify people’s voices — and using them for all sorts of other criminal investigations.”

Timm noted that in the last several years, whistleblowers, sources, and journalists have taken greater security precautions to avoid exposing themselves. But that “if reporters are using telephone numbers not associated with their identity, and the government is scanning their phone calls via a warrant or otherwise, the technology could also be used to potentially stifle journalism.”

For Timothy Edgar, who worked as the intelligence community’s first deputy for civil liberties, these risks “come down to the question: Are they looking for valid targets or doing something abusive, like trying to monitor journalists or whistleblowers?”

In some respects, Edgar said, speaker recognition may help to protect an individual’s privacy. The technology allows analysts to select and filter calls so that they can home in on a person of interest’s voice and screen out those of others. A 2010 SIDtoday memo emphasizes how the technology can reduce the volume of calls agents need to listen to by ensuring that “the speaker is a Chinese leader and not a guy from the doughnut shop.”

This level of precision is “actually one of the justifications the NSA gave for bulk collection of metadata in the first place,” Edgar explained. “One of the ways its program was defended was that it didn’t collect everything; instead, it collected information through selectors.”

At the same time, the very goal of identifying specific individuals from large patterns of data often justifies the need to keep collecting more of it. While speaker recognition can help analysts narrow down the calls they listen to, the technology would seem to encourage them to sweep up an ever-greater number of calls, since its purpose is to find every instantiation of a target’s voice, no matter what number it’s attached to. Or as the Pelton memo puts it, the technology gives analysts the ability to “know that voice anywhere.”

While these documents indicate that the agency sought to apply the technology to its employees, the documents reviewed by The Intercept do not explicitly indicate whether the agency has created voiceprints from the conversations of ordinary U.S. citizens.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act or FISA, gives the agency broad latitude to collect audio transmitted over foreign servers, foreign infrastructure, or from Americans communicating with foreigners. Because of this mandate, Edgar calls it “very conceivable” that voiceprints are being made from overseas calls. “It would surprise me if they weren’t deriving whatever intelligence they can from that data. It’s kind of their job.”

Experts strongly disagree, however, about whether the NSA would claim the legal authority to make voiceprints from the calls of American citizens on American soil, whose voices might be deliberately or accidentally swept up without a warrant. Part of this disagreement stems from the inadequacy of surveillance law, which has failed to keep pace with advances in digital technologies, like speaker and speech recognition.

While the U.S. has developed strict laws to prohibit recording the content of calls on U.S. soil without a warrant, no federal statues govern the harvesting and processing of voice data.

In part, this comes down to whether voiceprints count as content, which the government would need a warrant to obtain, or whether the NSA views voiceprints as metadata — that is, information about the content that is less subject to legal protection. The law is largely silent on this question, leading some experts to speculate that the NSA is exploiting this legal gray zone.

In response to a detailed list of questions, the NSA provided the following response: “In accordance with longstanding policy, NSA will neither confirm nor deny the accuracy of the purported U.S. government information referenced in the article.”

Illustration: Brandon Blommaert for The Intercept

A “Full Arsenal” Approach

ON THURSDAY THE Senate voted to extend Section 702 of FISA, which gives the NSA the power to spy, without a warrant, on Americans who are communicating with foreign targets. This reauthorization, which followed similar action in the House last week, has confirmed the views of critics who see the NSA taking an increasingly assertive — and ambiguous — interpretation of its legal powers.

Andrew Clement, a computer scientist and expert in surveillance studies, has been mapping the NSA’s warrantless wiretapping activitiessince before Snowden’s disclosures. He strongly believes the agency would not be restrained in their uses of speaker recognition on U.S. citizens. The agency has often chosen to classify all of the information collected up until the point that a human analyst listens to it or reads it as metadata, he explained. “That’s just a huge loophole,” he said. “It appears that anything they can derive algorithmically from content they would classify simply as metadata.”

As an analogy to how the NSA might justify creating voiceprints, Clement pointed to the ways in which the agency has treated phone numbers and email addresses. The XKeyscore program, which Snowden revealed in 2013, allowed agents to pull email addresses — which they classified as metadata — out of the body of intercepted emails. Agents also conducted full-text searches for keywords, which they likewise classified as context rather than content.

Edgar, on the other hand, says he would be taken aback if the government was making an argument that our voices count as metadata. “You could try to argue that the characteristics of a voice are different than what a person is saying,” Edgar said, “But in order to do voice recognition, you still have to collect the content of a domestic call and analyze it in order to extract the voice.”

It is not publicly known how many domestic communication records the NSA has collected, sampled, or retained. But the EFF’s Jamie Williams pointed out that the NSA would not necessarily have to collect recordings of Americans to make American voiceprints, since private corporations constantly record us. Their sources of audio are only growing. Cars, thermostats, fridges, lightbulbs, and even trash cans have been turning into “intelligent” (that is, internet-equipped) listening devices. The consumer research group Gartner has predicted that a third of our interactions with technology this year will take place through conversations with voice-based systems. Both Google’s and Amazon’s “smart speakers” have recently introduced speaker recognition systems that distinguish between the voices of family members. “Once the companies have it,” Williams said, “law enforcement, in theory, will be able to get it, so long as they have a valid legal process.”

The former government official noted that raw voice data could be stored with private companies and accessed by the NSA through secret agreements, like the Fairview program, the agency’s partnership with AT&T. Despite congressional attempts to reign in the NSA’s collection of domestic phone records, the agency has long sought access to the raw data we proffer to corporate databases. (Partnerships with Verizon and AT&T, infiltration of Xbox gaming systems, and surreptitious collection of the online metadata of millions of internet users are just a few recent examples.) “The telecommunications companies hold the data. There’s nothing to prevent them from running an algorithm,” the former official said.

Clement wonders whether the NSA’s ability to identify a voice might even be more important to them than the ability to listen to what it’s saying. “It allows them to connect you to other instances of yourself and to identify your relationship to other people,” he said.

This appears to be the NSA’s eventual goal. At a 2010 conference — described as an “unprecedented opportunity to understand how the NSA is bringing all its creative energies to bear on tracking an individual” — top directors spoke about how to take a “whole life” strategy to their targets. They described the need to integrate biometric data, like voiceprints, with biographic information, like social networks and personal history. In the agency’s own words, “It is all about locating, tracking, and maintaining continuity on individuals across space and time. It’s not just the traditional communications we’re after — It’s taking a ‘full arsenal’ approach.”

Documents published with this article:

Technology That Identifies People by the Sound of Their Voices

Still More on Tool Development

Open Source Signals Analysis: Not Your Grandfather’s SIGINT!

Human Language Technology in Your Future

For Media Mining the Future Is Now

CTIC: It’s Not Just Another Pretty Space

NSA Georgia Opens New Audio Forensics Lab

Alert: Voice Masking Is Discovered in SIGINT

Tips for a Successful Quick Reaction Capability

SIDToday Real-Time Regional Gateway Overview

SIDToday Voice Biometrics Capability

Finding a Modified Voice in SIGINT Traffic

Come to SID’s Identity Intelligence Conference

SIGINTers Use Human Language Technology to Great Advantage

How Is Human Language Technology Progressing?

RT Initiative Overview

Innov8 Voice Analytics Experiment Profile

Voice Fax User Group Minutes December 2010

Voice Fax User Group January 2008

Voice Fax Users Group Minutes October 2008

Voice Fax User Group Minutes March 2009