Write about my vision of a “post-capitalist world,” I was requested. But I find this difficult. Difficult because I believe we are already in, or nearing, a post-capitalist world if by capitalism is meant the system described by Marx and his followers about 150 years ago.

by Jeffrey Harrod Philosophers for Change December 31, 2013

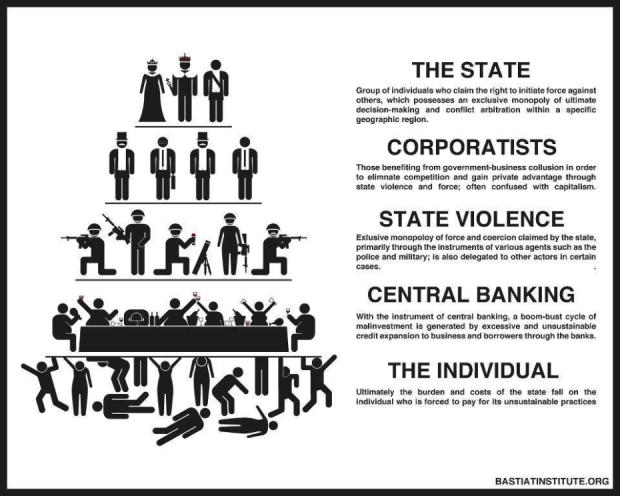

In this essay I raise the possibility for future discussion and action that there is an ongoing attempt to create a system for the maintenance of privilege and the production of poverty which is so different from the past that a new name should be found for it. Because a key component of it is the corporation it may be that corporatism is a suitable name.

Introduction: History as a succession of different ways to empower the rich

The French historian and progressive philosopher Fernand Braudel observed that throughout history there seemed to be a minority of people who held power and wealth, ruled society and exploited the population to sustain their power and privilege. If this were the case then the human history question of primordial importance is – “how does this minority do it?”

The answer to this question involves power. That is the concept with which social scientists, and particularly economists, have greatest difficulty. Power cannot easily be measured, the holders of power, unlike the weak, can resist being studied and the structures of power created are designed to prevent power being revealed. But equally there is always a resistance to power: so that the structure in which dominant power is set also has to deal with/eliminate/neutralize resistance.

From such a standpoint18th century capitalism as described by Marx is a successor form of domination and subordination which had historical antecedents of which feudalism is the most studied. If capitalism is production and distribution controlled by a small group of specifically identifiable persons, variously known as bourgeois, capitalists or power elites, then these conditions have existed since any recorded activity of humanity.

Subscribe or “Follow” us on RiseUpTimes.org. Rise Up Times is also on Facebook! Check the Rise Up Times page for posts from this blog and more! “Like” our page today. Rise Up Times is also on Pinterest, Google+ and Tumblr. Find us on Twitter at Rise Up Times (@touchpeace).

But every form of domination is different and certainly the 18th century model of capitalism was dramatically different from that which preceded it. In the 1700s the European enlightenment enabled a materialist view of the world. That power could be shown to be sourced overtly in the ownership of material, the means of production meant that the religious view that power could only be derived from God could be challenged.

However, there is clearly more to the nature of power, domination and exploitation than the simple ownership of capital, important as it is. Ideology, religious beliefs, prejudices, history of thought, cultures and ideas are all needed to create a stable system of domination where a minority extracts from the majority. Marx relegated such social and psychological forces to the “superstructure” and argued that they were developed from the struggle to divide up both the ownership and the fruits of production. Weber, Gramsci, Polyani, Mumford and now Bichler and Nitzan in their book Capitalism as Power and many others challenged this view but they only moved cautiously to the holistic idea that in order to establish domination and exploitation all aspects of humanity would have to be used.

If 1760 is taken at the starting point of the industrial revolution and 2014 as the contemporary period then three stages of capitalism can be seen. So, 1760 to 1890 is the development of a capitalist model as described by Marx in 1867; 1867-1970 as a hundred years in which major inroads into this model were made, and 1970 to the present when further changes occurred which raises the question of the viability of the early model. For convenience these are referred to at the 18th century model, the changes of the 20thcentury and the emergence of a new model in the 21st century, respectively. Periodisation is only to help understanding – history is a continuum so there should be no substantive arguments about the labels and periods made only for the sake of comprehension.

There is then a need to ask what the users of the idea of capitalism really mean in terms of power, both currently and historically. Of more importance perhaps is to consider the possibilities of a move from one form or system to another that will continue to sustain privileged elites and dramatic differences of material welfare within populations.

The 18th century capitalist model

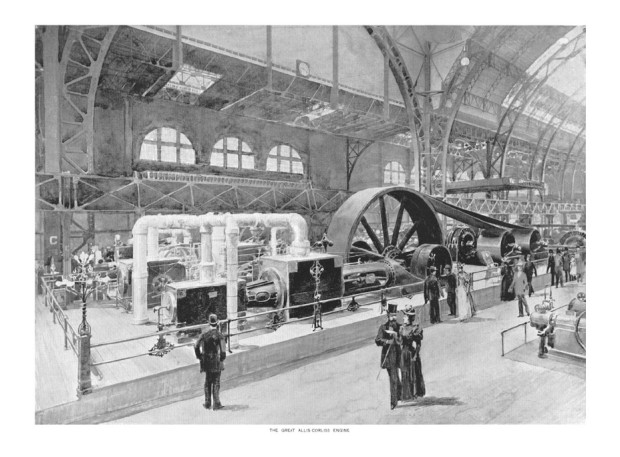

The origin of Marx’s description of capitalism was that of the 1700’s in the United Kingdom. Capitalism was then said to emerge at the same time as industrialism. Any attempt to disentangle the two is difficult. But there is some agreement that industrialisation emerged before capitalism which means that industrialisation could have well been the resistance to feudalism but which then later became captured by capitalists controlling the very means by which feudal lords were challenged. This observation is important because it indicates how systems of resistance are transformed into instruments of power.

What was new in 1700’s industrialisation was the form of domination and exploitation. There were four essential characteristics of this form: (1) power, which had been centred on feudal aristocracy and to a lesser extent governments, became dispersed to a large number of individual capitalists; (2) the factory form of production was introduced; (3) as a result for the first time a mass of workers were in the same place doing similar tasks; and (4) there was no moral, ethical or spiritual justification given for work undertaken by the factory workers or the social conditions which prevailed.

Not one land owner but many capitalists

Under Feudalism power was concentrated in the relatively few feudal barons, in kings and clan leaders and the officers of religion. The advent of capitalism dispersed the social power to a larger number of capitalists. The numerous mill and factory owners and their professional servants were the power successors to the feudal lord. Power in society became dispersed.

This dispersion of power caused Marx and his followers to identify a class of capital holders. Likewise classical economics could see the hundreds of individual firms headed by capitalists as a “market” in which they competed against each other. “Class” and “market” were the attempt to construct aggregates of power out of dispersed powerful individuals.

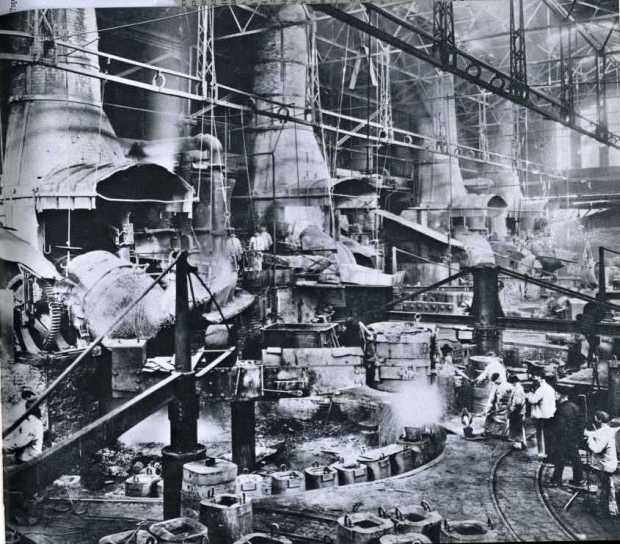

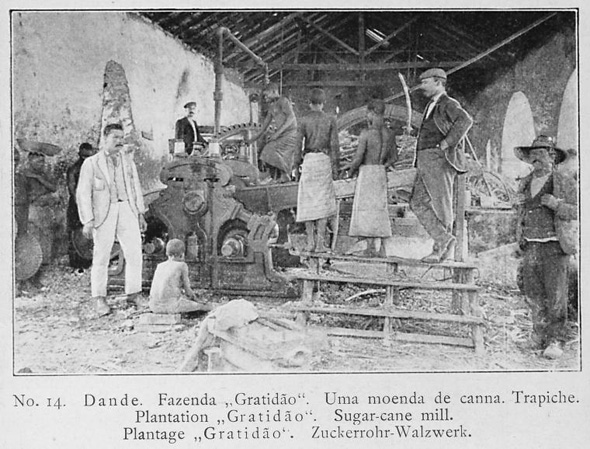

The factory form of production

What was more obviously new to the world was the factory system in which a mass of workers produced mass goods and, above all, were forced to work and be exploited because otherwise they would starve to death. This was indeed different from previous ways of disciplining and exploiting the poor in feudalism but from the standpoint of the poor the results were the same — crushing material poverty, low life expectancy from disease, malnutrition and inhuman work conditions. Despite all the historical hype proposing that the industrial revolution and capitalism meant an improvement for the poor, in the first 100 years of capitalism life expectancy in the UK only moved from 33 to 41 years.

Mass of workers

The development of a “mass” of workers was absolutely new. In the previous rural systems of exploitation, even on large farms, the workers were divided by space and by the different farms on which they worked. In France after land reform there were individual peasants and Marx described their revolutionary potential as low because together they were more like a “sack of potatoes” rather than a class. In the Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels talked of people in rural areas being condemned to isolation.

Marx’s lionisation of the mass of workers as the “working class” was understandable and his view that such a mass of workers could be the base for a revolution, at least on the surface, would appear to be well founded. The possibilities of agitation, education and collective action were certainly enhanced by the social proximity of a mass of roughly equally exploited people.

No reason given – just work or starve

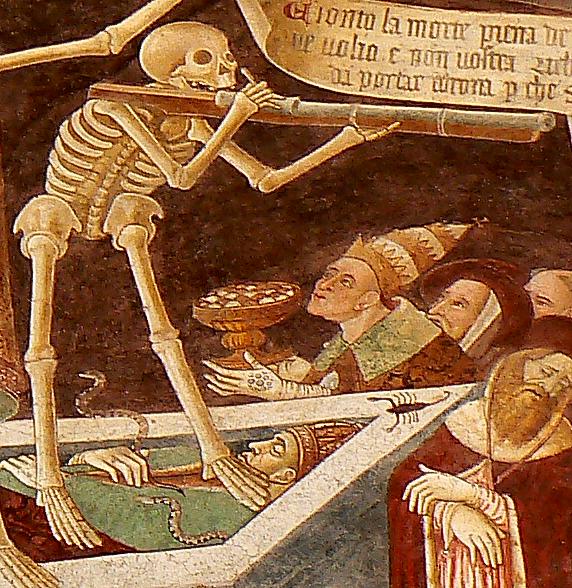

Perhaps, however, the most important difference between the new industrial/capitalist system and the old forms of exploitation of the poor was the absence in the new system of any justification for it. Prior to the industrial revolution each of the different systems of domination-subordination were accompanied by powerful psychological, non-material reasons for poverty. Peasants were pressured to believe in the “divine-right” of landlords, feudal serfs were told they needed the lords for security, lower caste members were told that the caste structure was necessary for an orderly and stable society as required by the gods. Even slaves we told that it was “‘Gods will” as claimed to be in the Christian bible that they were destined to be inferior and needed to be civilised by their owners. All of this was cemented into place by theology which preached the principle of the legitimacy of the existing power of the exploiters. These justifications associated with the feudal system started its dramatic decline with the French Revolution of 1789 when the lords lost their heads along with the myths concerning the divine need for aristocratic land ownership.

The industrial/capitalist system was then entirely different. The only way of dominating people and forcing them to work was the threat of starvation. For this to be a real threat the possibility of securing food and shelter other than from work in the factory had to be prevented. The work-survival connection was made permanent. No explanation for this was given. In a long discourse about wages and poverty Adam Smithgave no reason for the gruelling work other than that it would avoid starvation or secure “present subsistence”.

That Adam Smith should not refer to any higher or spiritual reason to work hard and long for a “superior” master should be of no surprise because he was just following a trend of the Enlightenment’s thinking. The philosophers of the Enlightenment, such as Spinoza, Locke and Voltaire, argued for rational, as opposed to suspect religious thinking; in doing so they provided the possibility of logical opposition to heredity and hierarchy and from that to the development of political theories of democracy.

But Enlightenment thinking also allowed the birth of a materialism based on economic production and it led to the proposition that work was only to secure the material (food, housing, clothing) necessary for survival. Thus, if work was lost starvation and early death ensued. This was considered the driving force of humanity and the motivation for work and production. In 1982, Paul Samuelson, a world famous American economist and text-book writer, said that the problem with the US economy was that “it lacked the hungriness motive.”

The 20th century challenge to the 18th century model of capitalism

The story, however, did not end with the establishment of industrialism and capitalism in the UK and elsewhere in the 19th century. The current discourse about “capitalism” in that sense is frozen in the 18thcentury model as described by Marx and based on his contemporary economists. In the 20th century there were changes which so weakened the nature of early capitalism that its relevance can now be questioned.

The changes and challenges to capitalism in the 20th century were: (1) the dispersed power to the individual capitalist was as re-concentrated — first, in the state and then in the corporation; (2) the factory form of production diminished; (3) the mass of workers originally associated with factories became globally dispersed and large numbers of workers were no longer needed for production raising the “surplus” labour issue; (4) in many countries of the world the “hungriness” motivation for work was severely undermined

The rise in the power of the state

The 20th century witnessed throughout the world the rise in the power of the state. The power of the bourgeoisie and of the “market” was constrained by the rise of the state especially in its redistributed form.

The relationship of the state to capitalism is controversial amongst Marxists because if the state was to change capitalism then it would not have been as Marx predicted nor for Lenin for whom the state was simply “the executive committee of the bourgeoisie.”

Outside the Marxist debate, however, it can be easily shown that the activities of the state in major economies and imperial powers between 1920 and 1975 profoundly affected the power of the 18th century type capitalists and, as will be noted later, undermined many other motivational aspects of the original model.

The core of this story rested on the state and its redistributive policies. There is a history to the level of state power. Perhaps the most important event was the coming to power of the communists in Russia in 1919. This meant that there was an extant form of confiscatory socialism in the world – a political regime in which the capital and material goods of elites were actually confiscated from them.

Furthermore, many advisors to elites had convinced themselves that Marx’s predication of the revolutionary potential of the pauperisation of the mass was true. The “material deprivation” theory of revolution was widely accepted. Mass agitation and social movements both labour and political also pushed the state into a redistributive role. It seemed then that state redistribution was the key; elite property would be relatively protected if material deprivation and pauperisation of the mass was prevented and the material conditions would be better for the poor.

In the Anglo-Saxon economies there were three markers of this development – Keynes’s pamphlet of 1929 in which he argued that the state should accept responsibility for full employment; the New Deal legislation in USA, 1933-36, in which Keynes was involved and the subsequent establishment of Welfare provisions in UK post-1945. The precursors to these developments were in Continental Europe and even in tribal cultures of Africa but the UK and USA were imperial powers which meant their institutions were spread around the world. The intellectual and technical basis of all these was Keynesian economics in which government expenditure was the key in managing material deprivation.

The state then redistributed throughout the 1930s and ‘40s. From the 1950s onwards “military Keynesianism” prevailed in the USA and elsewhere supported by the Cold War. The state retained its power basically via the military budget and the military hierarchy prevented the excesses of accumulation in the private sector which was witnessed in the last part of the century. In many countries in the 1970s the state was redistributing against the higher incomes to the extent of 50 percent of income earned.

In 1963, the outgoing US President Eisenhower warned against the dominance of a “military-industrial complex” as a threat to democracy but in 1980 the complex had reversed itself and it was now the “industrial-military complex” governed by corporations. This ascending semi-circular graph of state power is matched inversely by the accumulation of the top one percent in the USA. The percentage share of net wealth of the top one percent began to decline in the 1930s with the introduction of the New Deal and did not rise to even pre-1940 levels until the end Cold War in 1989 as the state began to lose control of private accumulation.

From the 1980s onwards the corporation in global sectors began to concentrate and their relative power increased – so by 1980 in the imperial countries the zenith of the state and its redistributive power had passed. The process of weakening state authority continued in the Global South through structural adjustment programmes.

These events in the 20th century did not destroy 18th capitalism as described by Marx but they changed its form significantly and had profound effects on the other distinguishing factors of the model.

The factory form of production in decline

The factory system was introduced as a control device in the 18th century model. Before that industrial production was by the ‘putting out system’ when textiles were produced on looms in workers’ homes and collected by a middleman to be sold by a merchant. Having workers in one place reduced supervisory costs and enabled the pace of work to be increased.

But as Marx predicted there was a contradiction in such a mass of workers because they took collective action and helped bolster the power of the state against the capitalists and corporations. So from the 1980s the factories in the major economies began to close — some scholars have argued this was the end of “Fordism” after the Ford motor company in USA (one of the first mass production factories).

It would be easy to believe that the factory system has declined in the rich and powerful countries only to be resurrected in the poorer countries to supply import. But that is only partially true because, for example, manufacturing imports from the whole world outside of the EU in 2011 was less that 20 percent of the total. What has happened is that manufacturing has become dispersed via outsourcing from large corporations and large-unit factory production has a massively reduced number of workers through automation, robotisation and digitalisation.

The question is how important was the factory system in the 18th century model? It was important as the principal instrument of disciplining and exploiting the workers in it. But it was also important as one of the contradictions of the arrangement – the mass of workers organised and became the principal and practical opposition to continued exploitation. On it was built the whole history of labour movements, social struggles and redistributive achievements. With its decline has come the fall in power of trade unions based on mass membership of one industry. The war cries based on the old history of trade unions now often fall on hollowed-out grounds. This was not the end of work-place collective action but the end of it as a major force in the 20th century.

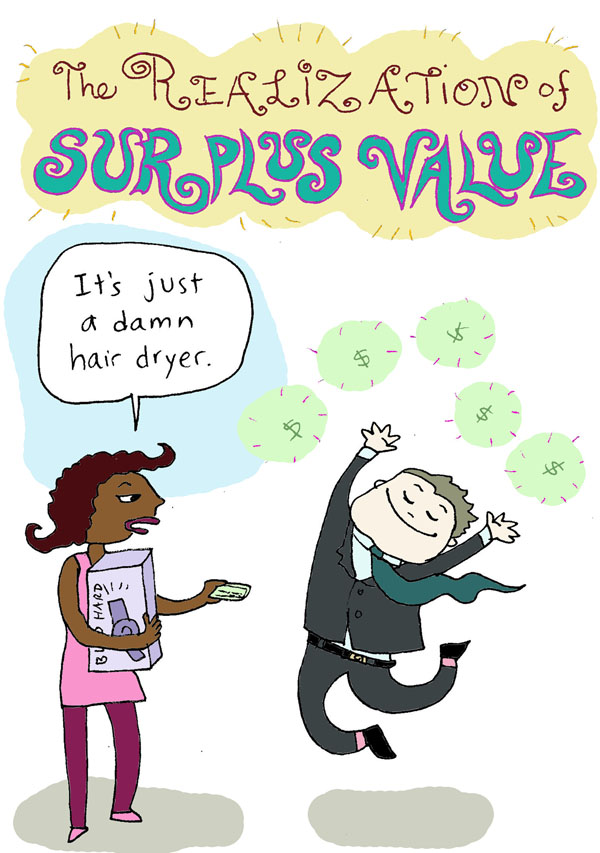

The Emergence of “surplus” labour

In the labour area there was always an important internal contradiction of 18th century capitalism. The reliance on material or economic coercion to make people work without support from religion, ethics, or moral ideas was always weak. So from the beginning it became clear that to maximise wealth at the top and avoid revolt and insurrection from the bottom fewer and fewer workers had to be used – in political economic terms the productivity of labour had to be raised. But both classical and Marxist theories of capital accumulation accepted that the rich would be richer (accumulation) if there was full employment. Marx’s labour theory of value meant that each capitalist extracted from a worker surplus value which meant that the more the number of workers the greater the surplus value. Bichler and Nizan writing in 2013 suggest that this is still the theory which capitalists pursue.

It was clear in the 18th century that there was a labour surplus what Marx called the ‘reserve army of labour’ which was developed through the general advancement of capitalism driving people from the land, from the changes in the needs of industrial production and from general overpopulation. This surplus labour and ‘reserve army’ played an integral role in the determination of wages and the general advancement of capital accumulation

However in the 20th century the increase in labour productivity anticipated by Marx was accompanied by the state attempting to control the size of the ‘reserve army’. In addition, the corporation did not act as an entrepreneur firm in relation to labour because of trade unions. The result was a mass of surplus labour which was not integrated into the capitalist system in a manner that had been expected in the 18th century model.

The extra productivity arising form automation, digitalisations and then robotisation started to make a permanent and impermeable divide in those that wanted to work. In the mid- 1990’s two German journalists talked of the “20-80 society” in which 20 percent owned or were permanent employers of production machines and 80 percent were basically excluded.

While 20-80 maybe an exaggeration the recent crises has easily demonstrated that the swaths of unemployment produced in countries across the world has not affected the top 20 percent of income and wealth holders. In London in 2011: an estimated 2.1 million people were decreed to be in poverty while in the same year 2,714 bankers mostly living in the London area earned over $3 million each. The top earners and those with well-paid and permanent work are beginning to be “ring-fenced” from the “underclass,” “working poor,” and other such labels applied to the people who cannot find a place of worth in the production system.

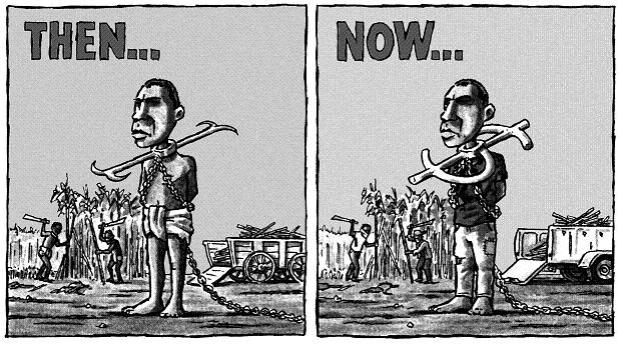

The result of this is a form of global ghetto-isation in which the poor are increasingly distinguishable by ethnicity or religion and effectively kept apart as an underclass. This has always been the case in the USA but it has a more recent introduction in Europe. It has been argued that this was part of an imitation of the American model – the insistence that the ethno-nation states should become the multi-cultural civic nations similar to that which is claimed for the USA. But this argument ignores that the same process of creating an unwanted labour force was inherent in Europe in the continued application of the policies of strong productivity growth and weak distributional mechanisms.

This has once again raised “the fear of the mass” so much a part of the mid 20th century. Is the development of mass marginalisation in fact Marx’s prediction of the “pauperisation of the mass”? The process bears little similarity with Marx’s under-consumption theory. Further, the political mobilising forces of these populations tend to be ethnicity and religion combined with social class but not class alone as in Marx’s mono-cultural, mono-religious model.

Religious mobilisation which has raised security issues throughout the world is sometimes seen as sourced in this development. Regardless of such speculation it again means that the 20th century model was drifting further and further away from the 18th century model.

The weakening of the hungriness motive

The original means of controlling work and labour was, as noted, the threat of starvation. At the beginning of the 20th century there was a move to a positive rather than a negative reward for part of the workforce – from “work hard or you will starve” to “work hard and you will get more”. This was partly an expression of defeat because it made the privilege of the rich dependent upon a continued and permanent increase in employed workers’ output (increased productivity and economic growth).

So movements which had a moral reason and ideology — in particular the labour (and to a lesser extent) the socialist movement — had considerable success against opponents who could have no resort to ethics. The result was that in industrially advanced countries of the world, starvation, death by untreated illness and low life expectancy was no longer accepted by populations who then looked to the state to create a “safety net” against life-destroying poverty.

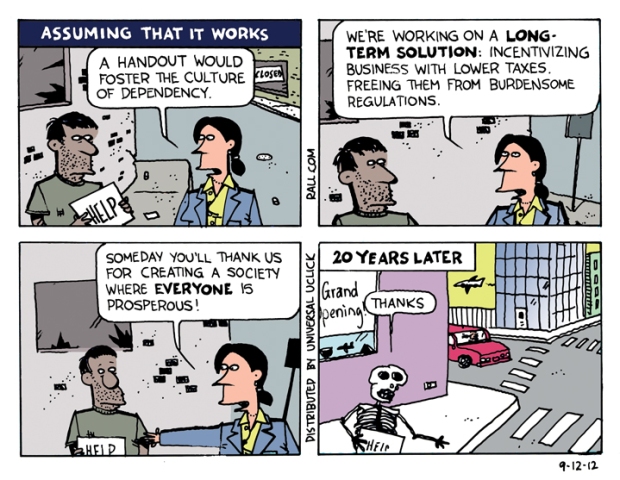

The disciplining function of “work or starve” was then lost as one of the key factors of the 18th century model. Without a strong and overt system of discipline and sanctions no form of extraction can have long-term stability. There have been attempts to restore hunger as a motivational force. Poverty and inequality has increased in the richest of countries. Poverty is increasing and will increase in Europe as the result of the austerity policies most of which have elements that make the loss of work materially serious.

Attempts to restore harsh conditions have been made at least since 1975. Yet government spending on welfare has not declined dramatically. Even extreme conservative governments have been forced to pass laws which placate the material demands of the underclass. One of these was ‘The American Dream Downpayment Initiative‘ (ADDI) signed by President Bush (junior) in 2003 which was the last of several acts to help provide houses to citizens who could not afford them. This practice of subsidising the US poor at the expense of the rest of the world was one of the causes of the 2008 so-called financial crisis. In other countries pressures to reduce or end social welfare have not been successful and welfare payments have remained stable or increased. A tough labour system was introduced into Germany which has resulted in about 16 percent of households in relative poverty (less than 60 percent of the median income). Yet recently the government was forced to introduce a minimum wage. Similar attacks on welfare provisions are faced with strong political opposition.

No system generating privilege and exploitation can be sustained without a powerful goad for people to work hard and long and to have a social discipline which prevents attempts at redressing of inequalities. Attempts to restore the hungriness threat have not succeeded or are failing. The 18th century model of capitalism is left without one of its principal mechanisms for survival.

So in the last quarter of the 20th century what has changed in the model that Marx described? The state increased its power and in doing so changed the power configurations between capitalists and corporations permanently, and at the same time laid an enduring resistance to exploitation based on the threat of starvation. Large masses of impoverished people were pushed outside of the capitalist system, and the mass production factory system is being replaced. These factors alone should cause reflection whether the 18th century Marxian model of capitalism can still deliver predictions and assist in the development of strategies for the 21st century. The importance of these changes has been recognised by some writers distinguishing the current period as “late capitalism”. It is suggested here that the changes do not merely result in versions of capitalism as in “early” and “late” but are an ongoing attempt to transform capitalism into another distinct regime creating privilege and poverty.

The 21st century attempt at transformation towards a new model

The last quarter of the 20th century until the present saw an acceleration of trends which had started earlier but which became proven and in some cases more noticed by mainstream observers. From 1970 four factors changed the 20th century nature of capitalism: (1) the rapid rise of corporate power changed the power structure of capitalism; (2) this event sets off an extreme rise in the power of financial corporations (banks); (3) there was an attempt to create a justification of exploitation based on the market; (4) the development of globalisation as practice and ideology to consolidate neo-imperial power of corporations.

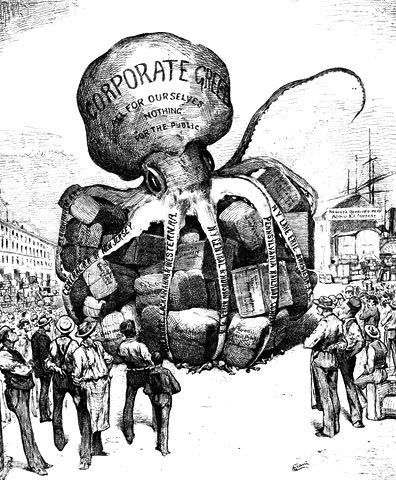

The dominant corporation

Since at least the 1970s there has been an ongoing and accelerating process of concentration of corporations in almost all global sectors. This means that by 2010 it is estimated that the global economy is controlled by about 200 corporations and banks.

This fact has yet to be understood by journalists, academics and producers of statistics who are still involved in the discourse and use of statistics which are provided as part of the economies of states rather than corporations. They are entrapped by the discourse and the residue of the zenith of the power of the state at the mid-20th century.

Seventy percent of world trade is controlled by multinational corporations; 30-40 percent from exchanges between the subsidiaries of the same corporation and a further 30-40 percent sales between different corporations. Ninety-five percent of all foreign investment is corporate. Yet statistics, academic papers and politicians’ arguments are still based on “foreign direct investment” rather than “foreign corporate investment” and inter-country (international) trade without ever mentioning the corporate presence. Smart-phones are not exported from South Korea they are exported from Samsung Electric Co., which controls 35 percent of the global market in these phones and contributed 17 percent of South Korean GDP. The US does not export disc operating system software, Microsoft does.

The power of the corporation is now a constant regardless of the political regime. The Chinese state-owned corporations (SOEs) are now listed with the so-called independent corporations from Europe, USA, Japan and elsewhere. While most commentators argued that SOEs are simply an arm of the state, deeper research would indicate that the relationship ‘party-state-corporation’ is not characterised by simply a dominance of one party. These Chinese corporations when they invest overseas begin to adopt the same strategy of action and finance as the non-state owned counterparts. How far Chinese foreign policy in Africa, for example, is corporation or state-driven is open for debate.

The discussions of the “globalisations” and international trade and investment in terms of state exports of goods and foreign investment are merely shadow discussions behind which are the corporate controls of these transactions.

The process through which the new situation has arrived is 30 years of corporate mergers and acquisitions on a global scale which has meant that almost every global sector is now governed by 2 to 5 multinationals. There is a rule of thumb used by economists that if 40 percent of sales are governed by 4 corporations or less in an industry then oligopoly exists. Such a narrow control of the industry would mean that almost all global sectors are technically oligopolies. The global wide-bodied jet sector has two dominant corporations — Boeing and Airbus; the disc operating software has one dominant corporation — Microsoft; the iron ore industry has two corporations, the cement industry five corporations.

Almost every sector shows a history of increasing concentration. The banana sector, for example, saw the top three US corporations Chiquita, Dole and Del Monte which in 1972 had 54 percent of the global market move to 66 percent in 2007. The top five banana corporations control 86 percent of the global production and consumption of bananas. Statistics from the USA show how fast this process is moving. In 2002, the top 10 banks controlled 55 percent of all US banking — today that figure is 77 percent. In 1983 — 50 media corporations controlled most of the news in the USA — the same news is now delivered by six corporations. Japanese corporations have always had quasi-monopolies internally despite the attempts to break up their internal empires after 1945. Japanese and Chinese corporations have developed regional spheres of power rather than global but this situation is changing fast.

The modern multinational does not compete in the product market as in the 18th century model. At the maximum there is “friendly rivalry” which does not affect prices as they would do in the classical model. When there is competition it tends to be nationally based rather than product based. Bichler and Nitzan claim that all corporations monitor the average return on capital invested and when their sector drops below that level they use their power to engineer an increase though political and social means including influencing states in relation to armed conflicts.

One study by a group of researchers from Switzerland has become well-known because they showed with mathematical sophistication in 2011 what Charles Levinson, an international trade unionist, predicted in 1969, that less than 200 corporations control the production and output of the world. The study looked as 43,000 multinational corporations and discovered, using network analysis, that 1,318 of them controlled the network and within that group there were 147 which in turn controlled more than 40 percent of the entire network. (“The network of global corporate control,” Stefania Vitali, James B. Glattfelder, Stefano Battiston).

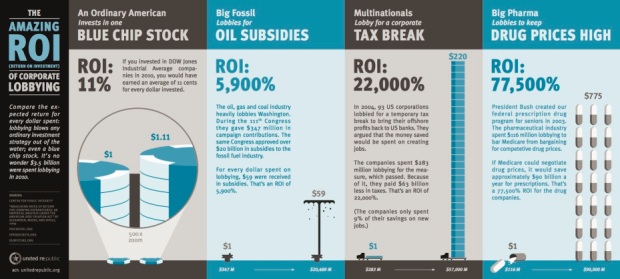

Adam Smith saw that firms became monopolies as the result of the tendency of businessmen to conspire to prevent competition. Baran and Sweezy in their book Monopoly Capital put monopolies at the centre of the economic scene. These arguments focussed on the economic aspects but none of them correctly foresaw the political rather than the economic form of monopoly.

The political form of the tendency to prevent competition is the modern global corporation which is far more than an economic monopoly or oligopoly dominating economic life by manipulation of prices and wages. The modern corporation is as much a political and bureaucratic entity as it is a monopoly enterprise. In maintaining the dominant position the corporation uses every element of societal existence. In the natural resource sectors corporations have become virtual state administrations. The modern corporation can hire private armies, which are also corporations, and can publish their views through the press which are also corporations.

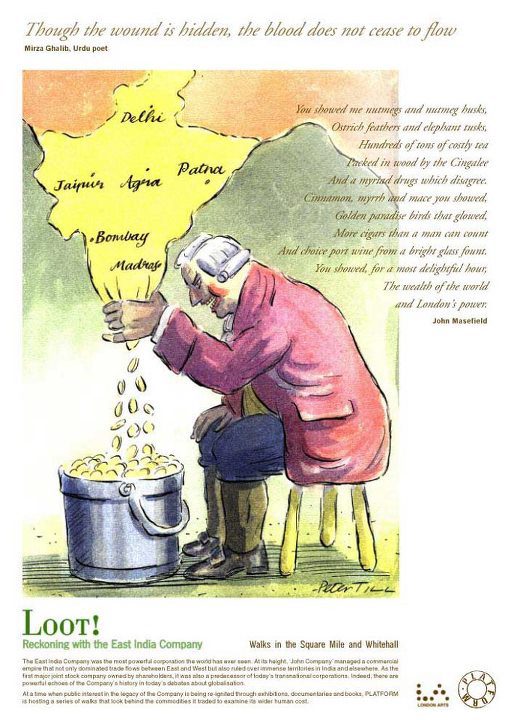

This is a new situation. When corporations dominated the world via imperialism they were state corporations supported by state monopolies in the imperial countries. State and corporation were merged as in the British, Dutch, French and Portuguese versions of the East India Company. Now the state merely supports the independent activities of its large corporations via diplomacy and consular services.

Today states and corporate elites are merging. More and more corporate chief executives are appearing formally and openly as heads of state/government. President Fox of Mexico came from Coco-Cola; Thaksin Shinawatra from mobile phones became prime minister of Thailand; prime minister Berlusconil in Italy stepped in from his media empire; Bush Jr., US President, was from an oil company; Mario Monti successor to Berlusconi in Italy was from the bank Goldman Sachs while Somalia appointed a businessman as prime minister in 2012. Some heads of government/state then become businessmen – in the Netherlands former trade union leader, then prime minister, Wim Kok went to the board of the Shell Corporation. This is no longer the so-called revolving door between the corporation and the state but rather the integrated entry to the world of power.

Multinational corporations are not transnational. They exist by manipulating the segmented labour and product market of a world divided into over 150 units. The surplus goes back to the headquarter countries. In some cases the surplus generated serve not only the rich in the headquarter country but sometimes to ordinary employers – profits made globally by General Motors go to help pay the health and pension benefits of retired workers in the USA.

Marx’s withering away of the state under socialism has become the withering away of the state in corporatism. Adam Smith’s hope that the laws would enforce competition failed, and Baran and Sweezy’s prediction of more imperialism to dispose of surplus did not foresee the global power of the corporation which adjusts capacity globally. The modern corporation has not only destroyed the market but has also assumed governmental functions.

Neither the neo-classical theory of capitalism nor the Marxists theory of capitalism can predict what a single corporation with 90 percent of its global market will do next year. The theories of behaviour are not equipped to deal with the processes of power in which the economic objectives are clear but the economic restraints are minimal.

The power of the modern corporation is in the process of replacing the capitalist of the 18th century with dominant owners and controllers of corporations and thus ushering in the 21st century’s corporatism.

Finance as a multi-level extraction process

All contemporary events and developments can be traced back to these transformational changes to the 18th century model of capitalism. In that model extraction from the working population was from manufacturing work in which the owner of capital took a disproportionate share of total productivity. Marx also saw that at some time and in some countries financiers would challenge manufacturing. In his analysis of French society he stated:

While the finance aristocracy made the laws, was at the head of the administration of the State, had command of all the organised public powers, dominated public opinion through facts and through the Press, the same prostitution, the same shameless cheating, the same mania to get rich, was repeated in every sphere…..to get rich not by production, but by pocketing the already available wealth of others. In particular there broke out, at the top of bourgeois society, an unbridled display of unhealthy and dissolute appetites, which clashed every moment with the bourgeois laws themselves, wherein the wealth having its source in gambling naturally seeks its satisfaction, where pleasure becomes crapuleux, where gold, and dirt and blood flow together. The finance aristocracy, in its mode of acquisition as well as in its pleasures, is nothing but the resurrection of the lumpen proletariat at the top of bourgeois society. – Marx, “The class struggles in France 1848-1850”, part 1.

This account appears to reflect almost exactly what is happening in Europe and North America today. But in fact this is not what is happening.

Marx thought the financiers were parasites and were in opposition to the industrialists and that the industrialists would fight back and eventually displace the financiers. His view, accurate at the time, was of a large number of industrial enterprises whose principal purpose was to extract profit from the population through organising work and manufacturing.

This is no longer the case. In the 1970s and 1980s corporations increased their oligopoly and monopoly position. This meant that when they needed finance they simply increased their prices to yield an investable surplus. The banks were then without their usual investment customers. But by mid-1990s financiers and industrialists saw the advantages of working together with the banks and finance as a multi-level means of extraction. Now the politically active corporations are either controlled by finance or there has been a cosy alliance between banks and corporations. The Swiss study quoted above claimed that a “large portion” of the control over the corporations which control global production and consumption “flows to a small tightly-knit core of financial institutions.”

This means that one of the new ways of exploitation in corporatism is through finance and debt rather than manufacturing. An employee sees part of his/her production taken by the employer as in the 18th century capitalist model, then a second part is taken as interest on his/her personal debt and then a further third part is taken through taxes to the owners of national debt. The debt parts of extraction are now greater than the production part.

This manner of extraction is practiced at all levels from individual to state. At the state level it reached a great level of sophistication in the 1980s and 1990s when applied to countries of the Global South and some East-European communist countries. The states were encouraged to take loans even under clearly unstable conditions. When the loans could not be paid back, sometimes because of the manipulations of raw material prices on which the states were dependent, the International Monetary Fund, backed by the financial sector, imposed penalties and sanctions on the governing elites unless they undertook ‘structural adjustment.’ One of the main features of this was to sell state assets at low prices usually to foreign corporations. The so-called ‘Third World Debt Crisis’ was not a crisis for the lenders – the debt was paid back to the banks and government and the corporations acquired valuable assets cheaply. This process is now being applied to some countries in Europe.

Marx was right about the behaviour of individual bankers and corporate chief executive officers but wrong about their collective behaviour — industrial corporations did not oppose the financiers. Under corporatism they allied with the bankers as another useful form of extraction. Corporatism unlike Marx’s capitalism does not rely on direct production and is able to integrate newer forms of mechanisms of control and extraction.

Neo-imperialism/globalisation

The ideology of the multinational is globalisation. There is one core reason for this. Globalisation is a process by which the state is weakened. Weakened, that is, at any attempt to control the economic destiny of its people via regulation at the borders or through internal political processes. A multinational has a single basic need which is access: to the economy, wealth, resources and labour of any country. Access-denying programmes are usually introduced by the state which in turn is connected by political movements that claim autonomy, sovereignty or are nationalist. The development in the 20th century convinced corporate elites that the major threat in the world would be the action of states. Major powers in the mid 20th century in the pretence of opposing communists were mainly interested in destroying the nationalist movements of already independent states.

The creation of corporatism is an imperial project – no information was given concerning the nationality of the 147 corporations in control of the global economy but just on the basis of the numbers of corporations in existence it is certain that they are predominately from Europe and North America.

Control and extraction from the global political economy is assisted by the activities of inter-state agencies at the universal and regional level. The corporations discovered that by working through existing inter-state agencies — the World Bank, the IMF, the UN or the EU – they could achieve outcomes that could have never been achieved by acting alone or at the national level. Once corporate power had increased on the domestic level it was a short step to allow the corporate and financial interests to “capture” inter-state organisations. The structural adjustment programmes executed in the Global South reached a level of imperialism which perhaps not even the original imperial powers could achieve based on the imperial policies of military oppression and divide and rule. Structural adjustment delivered the economy, lives and destinies of countries to the dictates of the IMF and World Bank themselves representing the core financial and corporate sectors. The policies that these latter proposed were to privatize, liberalise and economise. ‘Privatize’ to corporations, ‘liberalise’ to corporate products and ‘economise’ to serve debt repayments to banks. The EU, which is supposed to be neutral on the issue of public and private enterprise, recently agreed that privatization was a condition of receiving loans in Greece and Italy which are in part derived from European citizens’ taxation.

The economies of these countries were restructured to suit an imperial mandate which was to have unimpeded access for foreign banks and corporations. Indeed, for Lenin the state was the “executive committee of the bourgeoisie” under capitalism. Under corporatism the state is made a partner and previous state-constructed institutions became the global executive committee of the dominant corporations and banks.

The Market as a justification for inequality

The elites of corporatism are aware, it seems, that one of the weaknesses of the 18th century model of capitalism was the lack of a non-material justification for dominance and exploitation compared with other such systems. The exaltation of the market as an explanation for the outcomes in social affairs had been largely confined to theoretical economists rather than a general explanation for social ills and problems.

In the late 20th century, however, the market was launched to the public as an explanation for all social and economic events which might be ascribed to a policy, institution or person. The reason for the timing of the launch of the market as an explanatory myth is the arrival of corporate elites in positions of global and national power which challenge the state. At the very moment when the competitive market was destroyed by the monopoly or oligopoly of the corporation the market was launched on the world as an explanatory variable.

The corporation had arrived as a lead institution. Dominant institutions always had a non-material, mythical answer to questions concerning misery and inequality. In answer to the questions “why am I poor and others not” the religious\church’s answer was (and is) “it is God’s will”. When the state became the dominant power in many countries the answer to the same question was “it is the people’s will”. Now that the corporation is dominant the response is that “it is the will of the market.”

Thus the market is given as the explanation of austerity because “the financial markets demand” it, and for high executive salaries “we must pay the market price for these people”.

But compared with other justifications for poverty and exploitation based on religion, security or solidarity, the market explanation is extremely weak and gets weaker as the myth of it is exploded by revelations of fraud and collusion. The market is revealed in these cases as nothing but people manipulating policies directed at other people in order to secure material privileges.

As a justification for poverty and unemployment then it lacks the all-embracing power of the previous explanation for these conditions. In an attempt to boost its power it has been recently linked to democracy and human rights. The argument is that the ‘free market’ yields political freedom. The organisation of liberals, Liberal International, describes itself as the preeminent network for “promoting liberalism, individual freedom, human rights, the rule of law, tolerance, equality of opportunity, social justice, free trade and a market economy.” But the contradiction is that the greater the austerity, poverty and general un-social conditions, the greater the response for non-democratic controls and oppressions.

These attempts to attach more attractive ideas to the myth of the market has the same parallel with ‘free trade’ which has been presented for more than 150 years as a necessity for political freedom. Yet in 2008, the director-general of the World Trade Organisation talked of “restoring citizens’ confidence in trade” because, as with the market, citizens will no longer accept it as a governing force in their lives.

The 21st century transition from capitalism to corporatism?

In academic literature ‘corporatism’ is used to mean a political regime characterised by official representation at the level of the state of representatives of business and trade unions. The state in the theory was supposed to preside over mediation between the representatives for the common good. Its origins are from the Catholic Church in the late 19th century, a revised version by the fascist theorists of the 1930s and a further revised liberal version of the 1970s. It is said that corporatism was launched to prevent the class war predicted by Marx.

However, when this type of mediation was installed there was a tendency for the state to become dominant hence the expression ‘state corporatism’ which was associated with the dictatorships in Latin America and Spain. The more liberal version was named ‘social corporatism’ and was characterised by bargaining at the state level between business and trade unions – the so-called ‘social partner’ model of Continental Europe. There were other versions of this system – some one-party states in Africa and institutionalised one-party states in Sweden, Mexico and India were said to also be forms of corporatism.

So history has yielded a ‘state’ corporatism and a ‘social partner’ corporatism expressing the predominant holders of power in the system but never until the current period has there been an attempt at a ‘corporate’ corporatism in which it is the corporation and not the state that has the power to determine the core variables of any society.

The introduction as detailed above of dominant corporations, financial extraction, global access and market justification represent just such an attempt. An attempt to reconstitute the 18th century model as modified and weakened by the 20th century to make a new form or structure of extraction by a minority group from the majority for the 21st century. But it is an attempt not yet an achievement.

Any new model or construct must, as noted above, be able to deal with the contradictions inherent in action and counter action. In the current situation the contradictions, complexities and opposition may be greater than the attempt to move from capitalism to corporatism.

First, the 20th century rise of the redistributive state may have left a confidence in key populations that social justice is needed and inequality not acceptable. Major countries have not been able to completely destroy redistribution and welfare provisions and where it has been attempted it has been characterised by increasing political turbulence. Throughout the world populations are taking to the streets and expressing their anger through political action against corruption and governments not seen to be delivering social justice. A political reaction may not always be progressive or effective but for an analyst of political risk it is nevertheless a political reaction.

Second, the political reactions of the so-called underclass are not certain. Corporatism has produced a mass of marginalised and excluded people and at the national level often identifiable by ethnicity or religion. The greatest mobilising forces known to humankind – religion, ethnicity and belongingness are more powerful than the class motive alone as assumed by Marx. How far these will be used or can be used to disrupt the transition to corporatism is difficult to predict but this uncertainty itself means that the architects of the transition are faced with a potentially political opposition.

Third, the basis of the corporatist system is dominant corporations domestically and globally but the monopoly and oligopoly needed raise issues of functional efficiency. Without oversight and regulations based on the longer term issues of the general good, delivery of commodities becomes inefficient. How far ahead is the future for a corporate executive who is assured of a lifetime of excessive material benefits? Prudent investment for the future is not noticeable in large corporate finance. In addition, in the case of multinationals, ‘imperial dysfunction’ sets in when designs and decisions are made for a core market which does not suit the periphery. When material and technical efficiency declines under conditions when surpluses must be maintained fraud and criminality increases. The nature of the corporation at the core of corporatism may be the contradiction which prevents its complete fulfilment of the system.

Fourth, globally the opposing force to corporatism is sovereignty. The competition between corporations globally is based on nationalism rather than products in the Marxists and neo-classical view. When many countries in the world are capable of production and distribution within their own politically controlled area there is no reason to pass that power to a foreign corporation. Will the emerging corporations from outside Europe and North America be asked to join the global power cartel? Even if asked will they refuse?

The discussion in Europe about “competition” and the fear of rising countries elsewhere is not based on trade and productivity but on how long will such countries allow their domestic market to be controlled by foreign corporations. Japan has always resisted foreign corporate investment and indeed foreign investment is referred to as the ‘black ships’ of the original colonizing attempt of the USA. Western European and US corporations are aware that their dominance in foreign markets is in decline. The only solution would be to restore armed imperialism and that is constrained by the security potential of the major states of the world. Geopolitics does not favour the advent of corporatism.

Fifth, the financial form of extraction via personal and national debt is extremely volatile and precarious and yet it is an import element of corporatism. It is volatile because there is always a risk of a collective default. At the personal level the system can only be sustained with repressive instruments for servicing the debt. At the international level it is dependent on similar factors. That nations borrow to purchase essential goods not locally available can always be expected but when debt is incurred, as in the most recent cases to serve patronage demands and the inefficiencies of corporatism at the local level it leads to defaults and resistance.

Sixth, corporatism, lacking as it does any public good ethic, will continue the production-destruction and consumption growth paradigms of 20th century capitalism on which it has been partially built. These practices are at the core of resource depletion and environmental problems. Under the 18th century model of capitalism with its competitive production market it would be possible for the material constraints of environmental depletion to impact on the production process and objectives. Corporations face no such material pressures. As long as they can resists the weak environmental political pressures their decision-making will be short term and surplus maximising regardless of external or long term costs. Corporatism will certainly be as environmentally destructive as 20th century capitalism. Dealing with environmental restraints will also present challenges to those attempting the inauguration of the system.

Seventh, and finally, the market justification for all the problems currently encountered was already weak but is now defunct. The financial events of 2008 not only showed how the market was not working in finance but revealed daily how national elites who have become appendages to the corporate world were complicit in the development of these events. The serial failures of so-called market-based actions which usually meant either creating monopolies or passing from a state monopoly to a collusive private monopoly has finally enabled the myth to be broken.

These problems and weaknesses are and should be the focus for civil society opposition to the installation of corporatism. The modern corporation will not disappear but it may not be able to be the foundation of a successor to capitalism. From the above analysis it would seem the world is caught within a transition process in which there can be no going back but the future aims of global power may not be achieved and are not socially and humanly desirable.

This situation presents opportunities provided that the opposition can be forward-thinking and creative and not stuck fighting the current battles with the perceptions and tools of the past.

[Thank you Jeffrey for this groundbreaking essay]The writer is an essayist, researcher and academic in the fields of global political economy, labour and theory. He lives and works in the Netherlands. His website is www.jeffreyharrod.eu

If publishing or re-posting this article kindly use the entire piece, credit the writer and this website:Philosophers for Change, philosophersforchange.org. Thanks for your support.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.