Economic production and growth is not just about so-called survival, it is about power and control by man over as much as possible. This mindset is one of combativeness which also allows for exerting control over other beings and the environment so as to force extraction for one’s own interests.

***

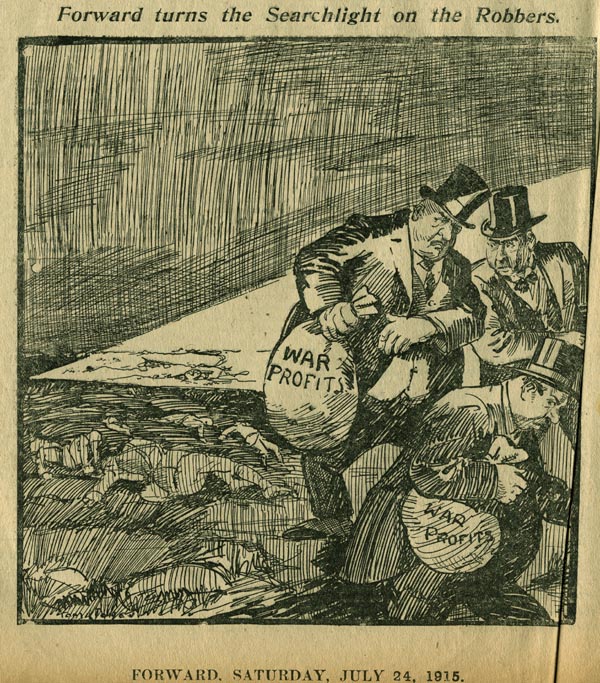

War production is the most vicious form of creating economic growth; it is a diversion of resources into an explosion of expenditure and wastage of anything that could be used to enhance and sustain life into everything that is destructive.

From ignorance lead me to truth

From darkness lead me to light

From death lead me to immortality — Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad, I.iii.28

By Sanjay Perera Philosophers for Change March 2016

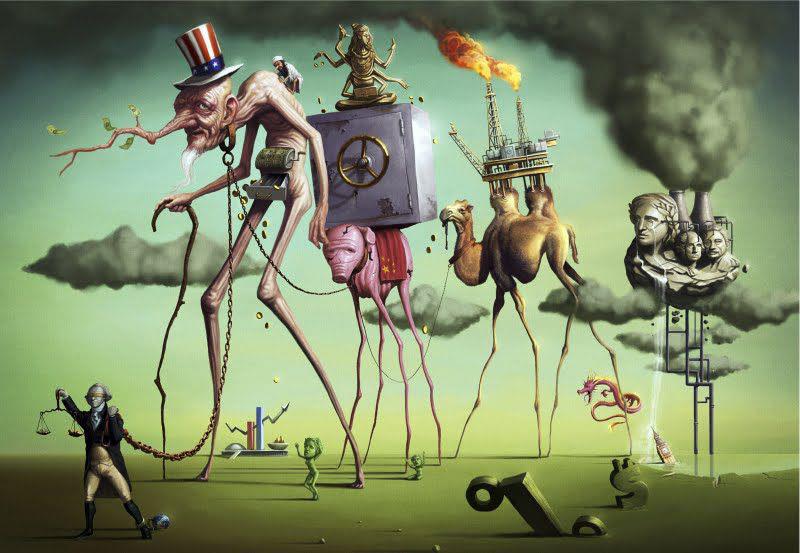

We are living in a time when the world is seeing the full effects of the economic violence of capitalism on all life forms and the planet itself. The violent process of capitalism is one of extraction and exploitation as it operates in a framework of polarity that exacerbates the difference between taking and giving, storing and sharing, and the separation between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’. Finally, its marauding intent shapes the outcome of who should live and who dies. This essay is also an interlude and bridge between Revolutionary constructivism and where the ideas here are meant to lead on to. The present piece is meant to fill a gap of sorts in the overall architecture in using the ideas of Immanuel Kant in understanding the moral underpinnings of revolutionary and radical thinking. It is also the prelude to examining the nature of capital, its use as a means of control and as an expression of power.

The Kantian mode of analysis is set out in Revolutionary constructivism as well as posts that are referred to within it. Similarly, within this mode of analysis the notion of waste, expenditure and surplus looked at here are synthetic ideas operating with a logic related to the idea of capitalism as most of us understand it. These ideas of waste, expenditure and surplus are sketched out in the context of the thinking of Thorstein Veblen, Georges Bataille, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The ideas will also be seen in relation to issues raised by Adam Tooze in The wages of destruction that deals with the economic motives behind the Nazi regime and WWII.

The activity of extracting resources, production and who gets to keep what in an economy takes place through the process of material-productive waste of resources and energy. Production is an activity that gives material support for people and one in which what is extracted is transformed into commodities. This production and its concomitant discharge of waste through exploiting surplus, also involves the expenditure of energy. However, the problem is that this process is in itself one that is wasteful primarily through the rampant expenditure of resources and energy which in turn seem to cause division in society aggravated by the mindset of lack, competition and fear.

A. Veblen’s theory of the leisure class

Perhaps Veblen’s best known work is The theory of the leisure class with its fascinating insights and satiric style. The exploitation that comes with production is emphasized early on,

…all effort directed to enhance human life by taking advantage of the non-human environment is classed together as industrial activity. By the economists who have best retained and adapted the classical tradition, man’s ‘power over nature’ is currently postulated as the characteristic fact of industrial productivity. This industrial power over nature is taken to include man’s power over the life of the beasts and over all the elemental forces (Veblen 6).

Media for the people! Click here to help Rise Up Times continue to bring you vital analysis of and commentary about current issues you won’t find in the mainstream corporate media.

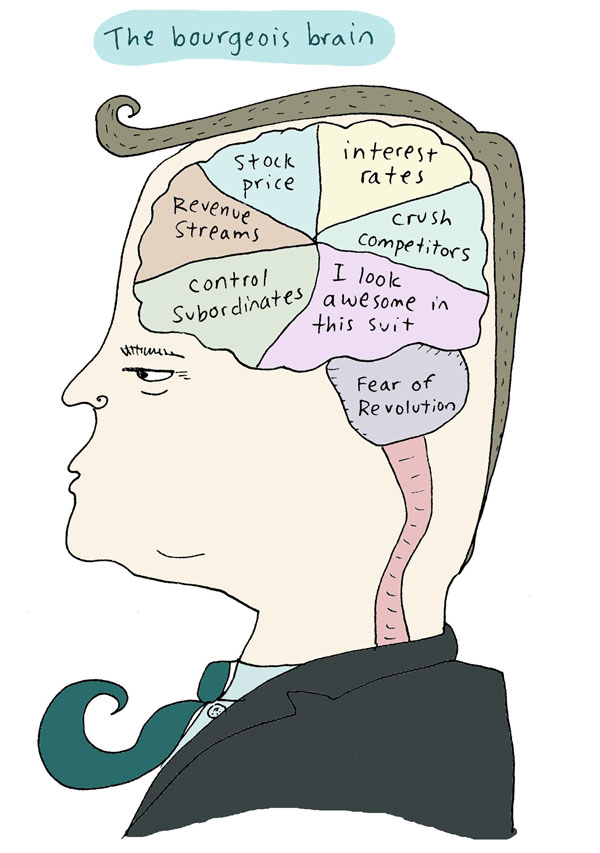

Economic production and growth is not just about so-called survival, it is about power and control by man over as much as possible. This mindset is one of combativeness which also allows for exerting control over other beings and the environment so as to force extraction for one’s own interests. Veblen describes this as a “habitual bellicose frame of mind – a prevalent habit of judging facts and events from the point of view of the fight” (Veblen 12). In the next lines this competitive and predatory attitude is also described as an “accredited spiritual attitude…when the fight has become the dominant note in the current theory of life.” How prescient Veblen is can be seen in the fact that his book was published in 1899 on the cusp of an ultra-violent capitalist century.

However, Veblen goes on to state that production of goods is not just for consumption but accumulation and ownership (and the status that accompanies this). In fact, accumulation is a function of status. This in turn is reflective of trying to emulate others (perceived as having status in society). So this possession of things is part of the ownership of wealth and the status that goes with it: Which thereby creates invidious distinctions (Veblen 17). He explains that the term ‘invidious’ is meant to be a technical one as “describing a comparison of persons with a view to rating and grading them in respect of relative worth or value” (Veblen 22). Hence, accumulation of commodities is part of soothing of one’s ego and a way to gain some form of respect and admiration from others; this certainly represents the consumer, advertising and marketing culture of today.

To Veblen part of the sense of privilege for the leisured and propertied class is to be able to while away time without doing anything useful as such. For the privileged ones wastefulness in terms of unproductive living is the way to go, so time “is consumed non-productively (1) from a sense of the unworthiness of productive work, and (2) as an evidence of pecuniary ability to afford a life of idleness” (Veblen 28). Hence, the need for servants and slaves to do the bidding of the leisured ones, in addition to their living ostentatiously while continuing invidious accumulation.

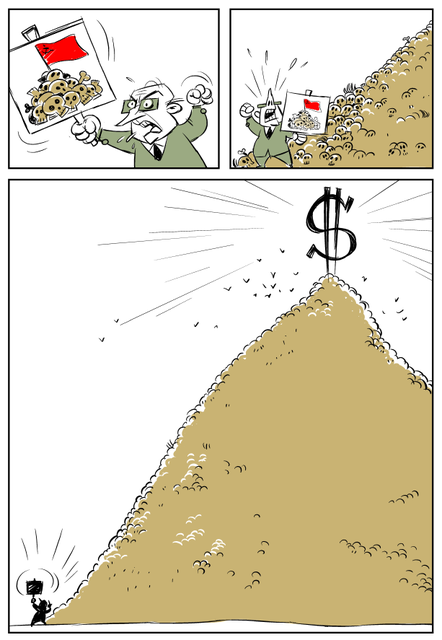

The situation has reached crisis point today when so many are caught up in a race of capitalist accumulation and the drive for profit has instituted modern slavery (to the capitalist paradigm of the supremacy of capital, banks and the political scoundrels serving them). People are treated as chattel and to be done with as pleased by those who believe they own people. The incentive for such ownership includes “(1) a propensity for dominance and coercion; (2) the utility of these persons as evidence of the prowess of their owner; (3) the utility of their services” (Veblen 34). This is a neat summary of the quest for control and domination that utilitarian capitalist principles have made the norm in our time. One only need see how the work force and those performing menial tasks are treated to grasp the veracity of Veblen’s words. In the next paragraph he sets out how people are treated as objects and indeed they not only provide a source of invidious accumulation but are also required as things to squeeze profit from: “Together with cattle…they are the usual form of investment for a profit….Where this is the case…the basis of the industrial system is chattel slavery…The great pervading human relation in such a system is that of master and servant” (Veblen 34).

The invidious accumulation of people and wealth is also, therefore, a means of exerting control. The use of industries can be seen as a means of not only production but of the exercise of control over production, accumulation of commodities and is further a form of domination over people. Many people have little choice but to work for their living with corporations, financiers, governments etc., which is, in the end, only a form of slavery that may occasionally allow you maintaining your tenuous keep.

Veblen then goes on to define one of his most famous ideas, conspicuous consumption. He compares conspicuous leisure with that of conspicuous consumption and both are wasteful activities. In the case of the former “it is a waste of time and effort, in the other it is waste of goods. Both are methods of demonstrating the possession of wealth” (Veblen 53). Ostentation is indeed the order of the day for some. This conspicuous consumption leads to conspicuous expenditure and is an expenditure of superfluities. Veblen tries to explain that he is using the term ‘waste’ in relation to consumption/expenditure in an economic sense of utility derived as the inevitable result of such a process; that is, the term is not meant to be deprecatory and he also calls it conspicuous waste (Veblen 60-61). But he then goes on to state that ‘waste’ does have a derogatory connotation when it is not shown to be useful in serving human interests. However, to Veblen ‘waste’ is there to “serve to enhance human life on the whole” (Veblen 61).

B. Bataille: A visionary of excess

While much of what Veblen says in terms of ‘waste’ and ‘expenditure’ overlaps with what is stated by Georges Bataille, the latter seems to develop a cogent basis for exploring these ideas in a broader and more intense socio-politico-economic framework. The early expression of Bataille’s ideas of ‘waste’ and ‘expenditure’ appear in his important 1933 essay “The notion of expenditure”. In the case of Veblen, he is content to show how economic utility is conflated within a system of conspicuous waste, consumption and expenditure and goes on to develop in his other work ideas relating to business, industry and capital. Underlying them is the idea of controlling people and resources, but with the sense that some of this is necessary for sustaining life as we know it.

But Bataille takes a different approach; one that is an offshoot of Nietzshe and revels in a form of orgiastic and destructive energy of creation, waste and expenditure. He also aims to give a systematic framework of how excess in the form of waste and expenditure is more an outlet for energy that must be spent, in one way or another, by human beings. Moreover, he sees capitalist excess as an idea that goes beyond Veblen’s invidious notion of the conspicuous: For Bataille capitalist excess is the means by which capitalists and the bourgeoisie not only use resources but consciously or otherwise destroy other life forms. This goes beyond just consumption – destruction becomes a way of life.

i. “The notion of expenditure”

Early in the essay Bataille discusses the idea of loss. He calls productive activity that which is necessary for the conservation of life and reproduction of societal and economic structures. Unproductive activities are that which appear to have no end beyond themselves and thereby are what he terms ‘expenditure’. Such expenditure would include mourning, war, cults, the arts, sumptuary monuments, spectacles, etc. (Bataille “Notion”, 118). In effect, such activities do not conform to the standard idea of economic utility. Expenditure involves a loss, that is, it involves significant waste of resources that have no link to utility as such. Bataille terms loss as “unconditional expenditure, no matter how contrary it might be to the economic principle of balanced accounts (expenditure regularly compensated for by acquisition)” (Bataille “Notion”, 118).

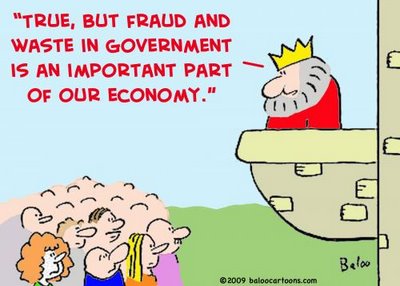

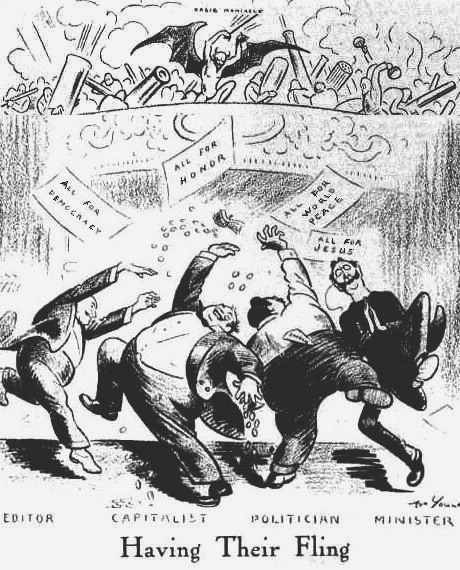

However, Bataille does seem to later conflate both economic and non-economic activities as the reverse side of expenditure; for in then end, both processes involve the use of energy and the creation of waste. He mentions that forms of war and destruction are as much a part of expenditure as is production. To him the hypocrisy of capitalists and the bourgeoisie arises in that their accumulation of wealth and status is at the expense (expenditure) of the ‘lower’ classes. He describes the process of the social reproduction and maintenance of the “representatives of the bourgeoisie” underlying such attitudes as “trickery [that] has become the principal reason of living, working, and suffering for those who lack the courage to condemn this moldy society to revolutionary destruction” (Bataille “Notion”, 124).

Next, Bataille expounds how the rich do not want to spend on the poor but prefer to consume the poor’s losses, thereby using the expenditure of one class of people as means of accumulation for another. This is the kernel of exploitation for Bataille, as the rich create for the poor (Bataille’s emphases) –

…a category of degradation and abjection that leads to slavery…the modern world had received slavery…and has reserved it for the proletariat…[A] bourgeois society…gives the workers rights equal to those of the masters, and it announces this equality by inscribing the word on walls. But the masters, who act as if they were the expression of society itself, are preoccupied…with showing that they do not in any way share the abjection of the men they employ. The end of the workers’ activity is to produce in order to live, but the bosses’ activity is to produce in order to condemn the working producers to a hideous degradation…” (Bataille “Notion”, 125-126).

The whole idea of accumulation is the heightening of expenditure against the interests of the common folk by those who exploit them. It is through this process that the negative effects of profit made and loss, in every sense of the word, is sustained by those who are exploited. It is a process that promotes a master-slave paradigm and condemns the majority of people to some form of depraved existence.

ii. The accursed share

In his great work in three volumes, The accursed share, Bataille looks at the economic forces of the world holistically as part of the energy that is the basis of everything. He states (Bataille’s emphasis),

…it is easy to recognize in the economy – in the production and use of wealth – a particular aspect of terrestrial activity regarded as a cosmic phenomenon. A movement is produced on the surface of the globe that results from the circulation of energy at this point in the universe. The economic activity of men appropriate this movement, making use of the resulting possibilities for certain ends….Is the general determination of energy circulating in the biosphere altered by man’s activity? (Bataille Share I, 20-21)

Here Bataille sets the stage for his analysis and examination of socio-economic-political forces as that which involve energy and expenditure – primarily through his notion of ‘exuberance’. He develops this idea by stating:

The living organism, in a situation determined by the play of energy on the surface of the globe, ordinarily receives more energy than is necessary for maintaining life; the excess energy (wealth) can be used for the growth of a system (e.g., an organism); if the system can no longer grow, or if the excess cannot be completely absorbed in its growth, it must necessarily be lost without profit; it must be spent, willingly or not, gloriously or catastrophically (Bataille Share I, 21).

In Bataille’s scheme, no doubt influenced by quantum mechanics, energy must be harnessed and used in one form or another. And the excess energy will be transformed creatively or destructively.

In line with his holistic view of economic activity Bataille, however, also states that one problem is that the economy is not always considered in simply general terms, and that economic activity tends to be viewed as a specificity without the appropriate context to interpret it in (Bataille’s emphases):

The human mind reduces operations, in science as in life, to an entity based on typical particular systems (organisms or enterprises). Economic activity, considered as a whole, is conceived in terms of particular operations with limited ends…Economic science merely generalizes the isolated situation; it restricts its object to operations carried out with a view to a limited end, that of economic man. It does not take into consideration a play of energy that no particular end limits: the play of living matter in general…On the surface of the globe forliving matter in general, energy is always in excess; the question is always posed in terms of extravagance. The choice is limited to how the wealth is to be squandered…The general movement of exudation (of waste) of living matter impels him [man], and he cannot stop it…it destines him…to useless consumption (BatailleShare I, 22-23).

Here Bataille expands on how energy and human life force is channeled and used productively and unproductively, but always as a way of extravagance/exuberance: So that no matter how many live in poverty or arguments made that necessities of life can hardly be linked to some form of wasted energy – the energy in itself cannot be accumulated “limitlessly in the productive forces; eventually…it is bound to escape us and be lost to us” (Bataille Share I, 22-23). Waste and entropy are inescapable.

Next, Bataille goes on to discuss the circulation of energy in human form and how the ground energy of humans in their quotidian activities needs to be channeled properly lest it take on (and as it also inevitably does via the capitalist paradigm) a destructive form. He notes astutely that it is the poorest economies that face blockages in the expression of this excess life force/ground energy. This in turn gets transmuted into wars and leads to further impoverishment of that society. The mishandling of this ground energy takes place through limited economic-political thinking that can lead to a situation of having to create diversions to channel this energy that may also entail wars as a means of expenditure/exuberance – on this last point Bataille is not explicit (Bataille Share 1, 23-24).

However, Bataille does make it clear later that energy that is blocked and not freely flowing and accumulated in a manner that causes income inequalities and lopsided wealth development will go through one form of massive expenditure, that is, war – which he calls an “immense squandering” (Bataille Share 1, 37). People become that portion that is expended as a sign of the surplus of wealth thatcan be wasted when not harnessed properly; it is also an expression of the loss of so much potential that in itself is immeasurable (the worth of a single life). This is also a “squandering without reciprocation”. For destruction of life implies the misuse of basic energy/life force or ground energy. And it is the lack of reciprocity and sharing of wealth — that which can remove blockages and allow for a smooth and equitable flow of ground energy — that underlies much of the privations of our lives (Bataille Share 1, 38-39).

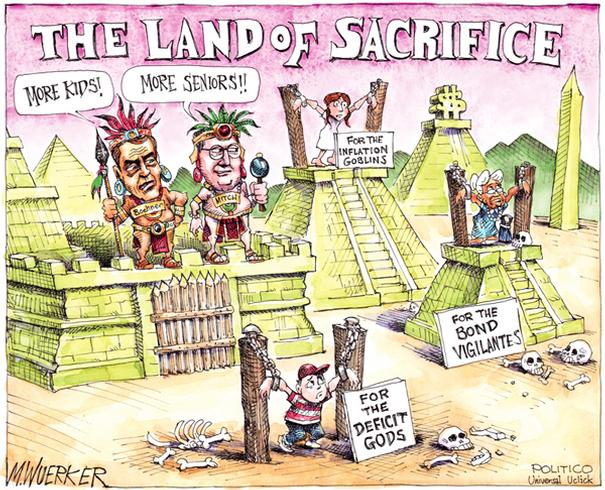

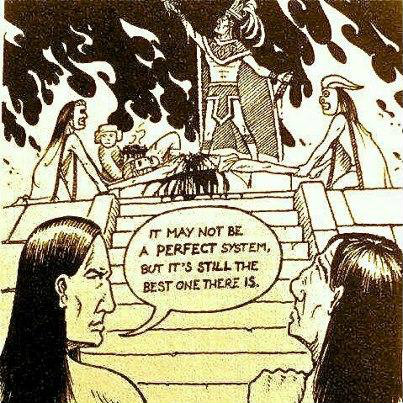

To Bataille, it is this sacrifice of human beings through war and other forms of unjust/harsh activities that marks them as the accursed share (Bataille’s emphases): “The victim is a surplus taken from the mass of useful wealth…and therefore utterly destroyed. Once chosen, he is the accursed share, destined for violent consumption.” These are the scapegoats selected to allow for the energetic imbalance of accumulation to continue for the benefit of some but at the expense of everything else. It is in effect a ritualistic economic culling or deliberate killing of humans that is needed to satiate the atavistic appetites of Moloch-Mammon. How little the human race has evolved in its antediluvian practices.

In a subsequent volume of this work, Bataille goes on to explain his idea of sovereignty. The basic distinction of sovereignty involves those who consume wealth as opposed to those that lack sovereignty and who are thereby left to produce the wealth without consuming it: “The sovereign individual consumes and doesn’t labor, whereas at the antipodes of sovereignty the slave and the man without means labor and reduce their consumption to the necessities, to the products without which they could neither subsist nor labor” (Bataille Share III, 198). This is a master-slave paradigm reproduced by capitalism within Bataille’s framework (which has Marxian roots). The necessities are produced to sustain the cogs in the machine, but the managers and manipulators can indulge in luxuries beyond rice or potatoes.

So the sovereign person has wealth to consume and waste at the expense of the vast majority. He consumes the “surplus of production” and does not in himself lead a productive life. This allows him to lead a life – Bataille’s emphasis – “beyond utility” (Bataille Share III, 198). The consumption of the sovereign one is at the expense of the energy and life force of those who have no choice but to produce. The production of that which is meant to have utility and create luxury for the exploiters is happily dumped time after time onto the shoulders of the majority. After all, where would we be without the expenditure of precious resources on Rolls Royces, Lamborghinis, Porches, the killings made in stock/money exchanges, or on those ever so elusive breakfasts at Tiffany’s.

This glorious expenditure/exuberance/human loss to create wealth and items of luxury is facilitated through a hierarchical division of labour that confers a higher rank on the exploiter than those who have to subsist through work (which is regarded as lowly). Therefore, those who work are meant to be seen as degraded beings (BatailleShare III, 248). Veblen would agree with this in that the sovereign/leisure class are meant to be those who indulge in conspicuous activity that invidiously reveal their elitist status as compared to those who do not measure up (in terms of income/wealth and accumulated commodities) to themselves. Sometimes this is called meritocracy. But it is almost always called democracy.

C. Marxian surplus

Needless to say the ideas of waste, exploitation and surplus work in tandem with those of Marx. And Marx’s interpretation and version of political economy offers an interesting comparison to that of Veblen and Bataille. His ideas of surplus value and exploitation evolve together with his ideas of capital. And it is the latter that is of prime interest to Marx in his political economy.

i. Grundrisse

In his notes, for what would eventually turn out to be Capital, called Grundrisse (or Foundations of the critique of political economy) – Marx states that wealth creation rests on disposable time. This is part of the connection between capital’s role in producing surplus labour that allows for surplus itself to be created continuously and thereby exploited. The existence of superfluous products (that which is beyond necessary products needed for labour to socially reproduce itself) is due to superfluous labour time. But with the use of capital (Marx’s emphases), “the existence of necessary labour time is conditional on the creation of superfluous labour time” (Marx Grundrisse, 398). This means that there is surplus/excess to be wasted and expended that allows for exploitation of the workforce to take place beyond producing what commodities labour creates for its own needs. It also implies labour’s enslavement to capital for in order to produce to survive, workers now need to produce that much extra to allow for capitalists to sustain themselves and profit from.

It is the surplus produce from surplus labour, which is extracted from living labour, that is subsequently transformed into capital which in turn is used to further exploit the workforce (MarxGrundrisse, 452). Marx goes on to explain how this surplus labour is commodified into necessary and surplus production which in turn is transformed into capital: This cycle then leads to not only alienation of the commodities from the worker but the means by which he is then made/exploited to repeat the whole process. This commodified and alienated labour (in the form of profit/capital) is like a scourge that whips living labour into performing its endless cycle of drudgery to serve the exploiters (Marx Grundrisse, 453-454). Man becomes a veritable Sisyphus wherein he is also punished into activity by the lashes of a beast called capital which is sown from a set of chimerical economic beliefs.

Later, Marx defines one of his most renowned concepts — surplus value — as the relation of surplus labour to necessary labour; that is, whatever the worker produces beyond what is necessary for himself is the surplus value which is exploited by the capitalist. The worker helps create the capital which in turn makes him subservient to it (Marx Grundrisse,764).

ii. Capital: Volume 1

The idea of surplus value is discussed by Marx at greater length in his groundbreaking first volume of Capital. He stresses that what distinguishes “the various economic formations of society – the distinction between…a society based on slave-labour and a society based on wage-labour – is the form in which this surplus labour is in each case extorted from the immediate producer, the worker” (MarxCapital 1, 325). But in either case it is an extraction from/exploitation of people and in the case of the wage-slave (that is, most of us) the extraction is via the instrument of capital.

In his chapter on “The working day” Marx is eloquent about the injustices of what capital does to people. In a passage worthy of some of the famed literary works of the latter half of the 19th century he proclaims how dead/reified labour in the form of capital is used to suck up the life force (ground energy) of workers to feed itself, and continue expanding at the expense of life itself: “Capital is dead labour which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks. The time during which the worker works is the time during which the capitalist consumes the labour-power he has bought from him. If the worker consumes his disposable time for himself, he robs the capitalist” (Marx Capital I, 342).

So the capitalist survives off the life force of others whose surplus produce he sells to sustain himself while in effect also robbing the worker of his products that emanate largely through his expended life force. If the worker could only keep the use of his time and life force to do as he wants for his own good, he would in effect drive a stake through the heart of the capitalist (who thrives on the stolen time and life force of others).

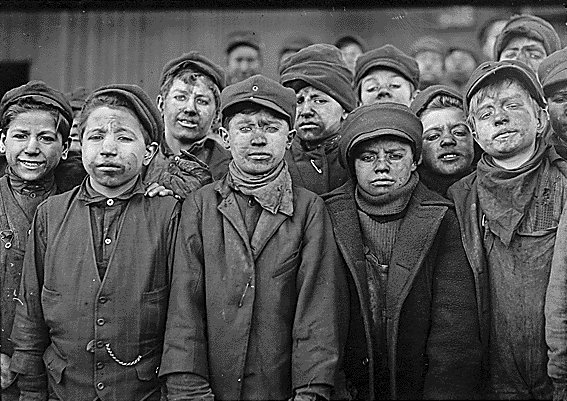

In full gothic mode, Marx goes on with another image on the impact of capital on the lives of the many. He mentions how the working day is cruelly extended so that all who labour for that crust of bread must do so to the point that it in one way or another kills them. He adds that “the werewolf-like hunger for surplus labour, in an area where capital’s monstrous outrages, unsurpassed…” needs regulation for all forms of work so that there are fixed hours to the working day (MarxCapital I, 353). Not being able to afford silver bullets to fend for themselves, children are subject to abuse: Those aged 7 to 9 years worked 15 hour days, six days a week – all in the name of profit accumulation. This waste of human life force intrinsic to the production cycle is described by Marx as a means of “physical degradation…premature death, the torture of over-work” (MarxCapital I, 381). And on the next page we learn that the state needs to interpose laws to protect abuse in the “transformation of children’s blood into capital.”

The coercive nature of capital is explored when Marx states that it “compels the working class to do more work than would be required by the narrow circle of its own needs. As an agent in producing the activity of others, as an extractor of surplus labour and an exploiter of labour-power, it surpasses all earlier systems of production, which were based on directly compulsory labour, in its energy and its quality of unbounded and ruthless activity” (Marx Capital I, 424-425). Not just the financial, but technical advances in capital (in the sense of technology and equipment) are also instrumental in creating an engine of slave-driving that extorts the maximum from human beings while giving the minimum to ensure they survive to keep this inhuman rigmarole in operation.

Yet this capitalist system even with its technological advances “while it enforces economy in each individual business, also begets, by its anarchic system of competition, the most outrageous squandering of labour-power and of the social means of production…In capitalist society, free time is produced for one class by the conversion of the whole lifetime of the masses into labour-time” (Marx Capital I, 667). The idea of waste and squandering of life energy (ground force) — as Bataille would agree — is essential in the capitalist system of exploitation of surplus energy for production via the expenditure of human life (or any other life form).

And Marx also adds: “Capital…is not only the command over labour…It is essentially the command over unpaid labour. All surplus-value…is in substance the materialization of unpaid labour-time. The secret of the self-valorization of capital resolves itself into the fact that it has at its disposal a definite quantity of the unpaid labour of other people” (Marx Capital I, 672). It is by not remunerating people fully for what they produce that allows capitalists to make a profit. Not only is capital used as a means of exerting control — it is the catalyst for extracting value/profit from human beings at their expense but to the benefit of their exploiters. So the surplus produced for the bosses — which allows them to support and enrich themselves — is only possible because of unpaidlabour: It is because people are not ever fully paid for their productive work, that allows for that surplus from which profit is generated.

And this vicious cycle of capital adding value unto itself/accumulating is endemic to the capitalist system; it is possible due to the waste and expenditure it revels in via that labour which is not paid for the surplus it produces. This is enhanced by the existence of the encampment of the ‘reserve army’ of the unemployed that is always a sign of capital’s brutal activity in whichever society it invades.

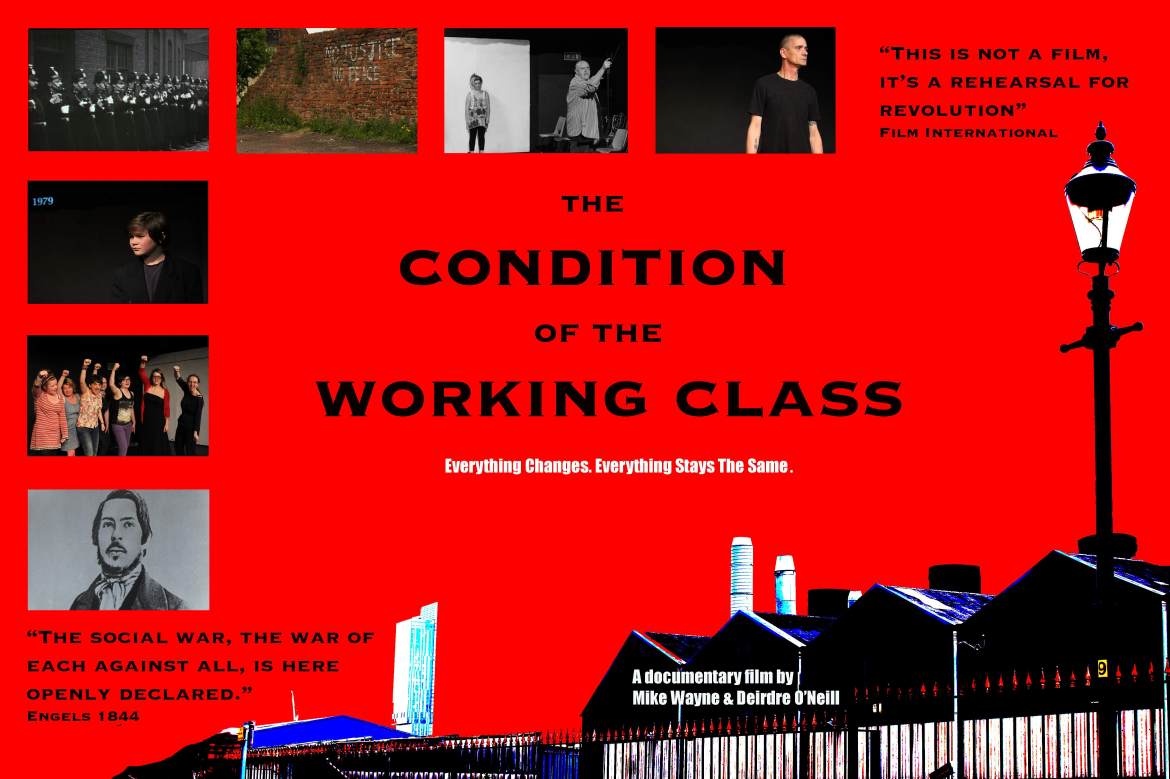

D. Engels and the working class, et al.

Before his great friendship and collaboration with Marx, Friedrich Engels when still in his twenties wrote a remarkable work while a businessman in Manchester. The condition of the working class in England is a classic that has much that is prescient and alarmingly relevant till this day as to what is happening throughout the globe. It is hard to believe that the book is a product of 1844 when it describes scenes in the metropolis of London (which could apply to any capital city). He creates a sharp sense of the teeming alienation of individuals in a society that was part of an empire. At the heart of the big city we have people who throng –

by one another as though they had nothing in common, nothing to do with one another, and their only agreement is the tacit one, that each keep to his own side of the pavement, so as not to delay the opposing streams of the crowd…The brutal indifference, the unfeeling isolation of each in his private interest becomes the more repellent and offensive…And, however much one may be aware that this isolation…this narrow self-seeking, is the fundamental principle of our society everywhere, it is nowhere so shamelessly barefaced, so self-conscious as just here in the crowding of the great city. The dissolution of mankind into monads, of which each one has a separate essence, and a separate purpose, the world of atoms, is here carried out to its utmost extreme (Engels 69).

A city and world driven by commercial enterprise at the expense of all else is what the modern world has become; where the only thing that matters is some form of financial currency; human decency is secondary to pecuniary interest. Driving home the message of how capital is a mode of control over people, Engels continues with:

Hence it comes, too, that the social war, the war of each against all, is here openly declared…people regard each other only as useful objects; each exploits the other, and the end of it all is, that the stronger treads the weaker under foot, and that the powerful few, the capitalists, seize everything for themselves, while to the weak many, the poor, scarcely a bare existence remains.

What is true of London…is true of all great towns. Everywhere barbarous indifference, hard egotism on one hand, and nameless misery on the other, everywhere social warfare, every man’s house in a state of siege, everywhere reciprocal plundering under the protection of the law, and all so shameless, so openly avowed that one shrinks before the consequences of our social state…and can only wonder that the whole crazy fabric still hangs together (Engels 69).

The words speak for themselves, as do the ones immediately following:

Since capital, the direct or indirect control of the means of subsistence and production, is the weapon with which this social warfare is carried on, it is clear that all the disadvantages of such a state must fall upon the poor man. For him no one has the slightest concern. Cast into the whirlpool, he must struggle through as well as he can. If he is so happy as to find work…if the bourgeoisie does him the favour to enrich itself by means of him, wages await him which scarcely suffice to keep body and soul together; if he can get no work he may steal…or starve, in which case the police will take care that he does so in a quiet and inoffensive manner…But indirectly, far more than directly, many have died of starvation, where long-continued want of proper nourishment has called forth fatal illness…The English working men call this ‘social murder’, and accuse our whole society of perpetrating this crime perpetually. Are they wrong? (Engels 69-70).

Not only do we see the division of society into ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’, but the use of capital as a tool of control and destruction. It is far more than just a productive device — it is a means of subjugation and decimation. The sense of atomization and loss pervades a society that is based on the systematic expenditure of its workforce via the deleterious activities of capital. As Engels goes on to say, “Every working man, even the best, is therefore constantly exposed to loss of work and food, that is to death by starvation…” (Engels 108). For it is only a matter of capital flowing away from one place to another that will leave even the most productive worker high and dry and free of everything except want.

This sense of blockage of ground energy of not sharing and hoarding, as Bataille mentions, gathers up into a negativity that is re-channeled into further need to waste life and resources through violence. And so, “the ‘surplus’ who has courage and passion enough openly to resist society, to reply with declared war upon the bourgeoisie to the disguised war which the bourgeoisie wages upon him, goes forth to rob, murder, and burn!” (Engels 120). Misused energy which is set up as opposition rather than one of mutual aid and support inevitably leads to destructive outcomes.

This is compounded by the social murder that takes place through a system that robs the life force of humans for the leisure and luxury of the few. Engels states that thousands living in dire straits are forced — “through the strong arm of the law, to remain in such conditions until that death ensues which is the inevitable consequence…its deed is murder just as surely as the deed of the single individual; disguised, malicious murder, murder against which none can defend himself, which does not seem what it is, because no man sees the murderer, because the death of the victim seems a natural one…But murder it remains” (Engels 127). This emphasis on destruction is hardly exaggerated as capital is used broadly and precisely as a tool to create waste and social expenditure that involves ruin and death for many: Not just physical, but mental, emotional and spiritual.

The harshness of the ‘free market’ capitalist indoctrination of his day, which extends to ours, made Engels write:

…the rest of the adherents of free competition [believe] that it is best to let each one take care of himself, they would have preferred to abolish the Poor Laws altogether. [But]…they proposed a Poor Law constructed as far as possible in harmony with the doctrine of Malthus…We have seen how Malthus characterizes poverty, or rather the want of employment, as a crime under the title ‘superfluity’, and recommends for it punishment by starvation…”Good,” said they [Poor Law Commissioners], “we grant you poor a right to exist, but only to exist…You are a pest, and if we cannot get rid of you as we do of other pests, you shall feel, at least, that you are a pest, and you shall at least be held in check, kept from bringing into the world another ‘surplus’…Live you shall, but live as an awful warning to all those who might have inducements to become ‘superfluous’” (Engels 283-284).

Here the idea of superfluity is taken to the extreme of treating people as pests who need to be curtailed and kept in workhouses where some of the most degrading abuses took place. By many of the poor, the workhouse was regarded as a variation of hell. Here we see the commingling of how the idea of surplus energy is turned into that of superfluous people who are then the excess that must be contained and somehow removed, one way or another, not to get in the way of the Malthusian pyramid of survival of the leisure classes at the top — who build their luxuries through the life suppressed and ruined at the base.

And referring to an earlier period in England in The London hanged, Peter Linebaugh describes the superfluity of humans regarded as surplus as the urban “proletarians [who] lived in dirt; they lived by an economy of wastes; they were part of a ‘marginal’ or ‘disposable’ population” (Linebaugh 149). The flotsam of society were just so much ‘waste’ that needed to be discharged and distanced from of as much as possible such that Engels gives a shocking account of how the dead of the poor were treated. The pauper burial-ground for the dead from the workhouses reflected their status for they were —

…dumped into the earth like infected cattle…[It was the] resting-place of the outcast and superfluous…It was not even thought worth while to convey the partially decayed bodies to the other side of the cemetery; they were heaped up just as it happened, the piles were driven into newly-made graves, so that the water oozed out of the swampy ground, pregnant with putrefying matter, and filled the neighbourhood with the most revolting and injurious gases. The disgusting brutality which accompanied this work I cannot describe in further detail (Engels 287).

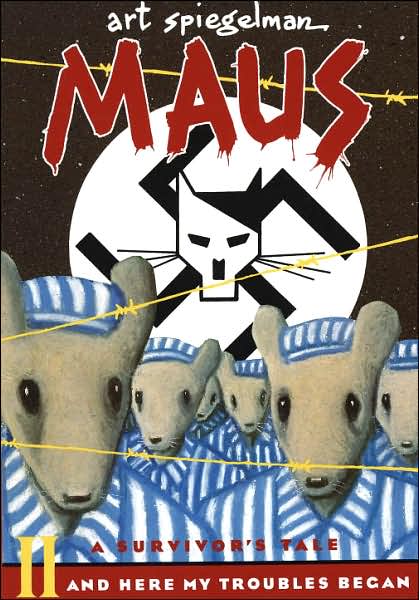

This also brings to mind the words of Laura Hudson when she writes (and quotes from Giorgio Agamben’s Homo sacer) about the superfluity of humans in the form of the Jews, who were executed under the dictates of Nazi biopolitics:

The program of euthanasia morphed into a program of genocide, in part, because the lives of the Jews were determined to be lives devoid of political value and, as such, not worth living. The Nazi program of euthanasia against the mentally infirm…was carried out…in spite of the burden it imposed on the Nazi war effort. Its importance lay not in the practical considerations of preventing the incurably ill from reproducing but in cementing the sovereign power of the Nazis and the Fuhrer to determine the value of life…Those placed in concentration camps were no longer citizens…Their deaths were not murder because their lives had already been determined to have no value. Thus, Agamben argues, it was not as a punishment that Jews were sent to the camps…“The truth…is that the Jews were exterminated not in a mad and giant holocaust but exactly as Hitler had announced, ‘as lice,’ which is to say, as bare life.”…Nazi politics was not directed against Jews as citizens or even an ethnic group, but was a politics in which Jews (and others) were no longer considered human…People [today] are increasingly seen less as citizens invested with political rights than as bodies in need of administration. Not only are they denied the promise of the “good life,” they cannot even expect a “good death” (Hudson 22-23).

What this reinforces is that the idea of waste, excess and surplus results not only in the kind of economic growth that we know today, but it is a form of human expenditure that dovetails with destruction through violent social and political ideas that rationalize the process of getting rid of undesirables. It is not coincidental that Nazi biopolitics takes place within a society and economy honed for war. The climactic enactment of expenditure for the Nazis is the treatment of life as an excess that must be sacrificed in a brutal ritual for there to be enough (or to maintain that perception) for those who were to be left to experience a Thousand-year Reich. Just as there can never be enough excess for the Nazis, there is no such thing as enough for the capitalist system in terms of commodities and luxury goods to be created. Anything that is deemed as excess to this relentless and soulless materialistic economic drive always needs to be used up callously and destroyed in the process: This is, unsurprisingly, one of the underlying principles of war which is about grabbing-hoarding and the antithesis to sharing or spreading resources and gifts all around.

E. Tooze’s wages and destruction

One of the main ideas that Adam Tooze proposes in his important book on the Nazi economy, The wages of destruction, is that Hitler saw America as the main competitor to Germany and was intent on securing as much of a hinterland and economic base in which to win that race for supremacy. His idea of Lebensraum was driven by his Darwinian notion of life which underlay his quest for dominance and control (Tooze 145). And wasteful expenditure was indeed the underlying motif of the Third Reich. War production is the most vicious form of creating economic growth; it is a diversion of resources into an explosion of expenditure and wastage of anything that could be used to enhance and sustain life into everything that is destructive.

This even led to enforced massive wasteful leisure activity which would have shocked even Veblen. For instance,

…the reintroduction of conscription in 1935 amounted to an enormous collective holiday for millions of young men, who were fed and clothed at public expense whilst not engaged in productive labour. It is hard to deny…that there is a degree of parallelism between various mass youth organizations of the Nazi party, the organized collective activity of the military and the organized mass leisure activities of the Kdf (Kraft durch Freude)…At a symbolic level…the Wehrmacht formed the centerpiece for many of the ritualized mass events of the regime. From 1934, the ‘Day of the Wehrmacht’ was to become a popular fixture at the Nuremberg party rallies, featuring tens of thousands of troops, thousands of horses and vehicles including entire regiments of tanks and elaborately choreographed mock battles…[T]here can be little doubt that the rearmament in the 1930s was as much a popular spectacle as it was a drain on the German standard of living, a form in other words of spectacular public consumption (Tooze 163-164).

This wasteful expenditure of resources and diversion of human energy away from anything positive towards self-serving propaganda fine-tuned towards unleashing destructive energy in the world is perhaps a perfect fit for Bataille’s idea of expenditure-exuberance. Tooze sums this up further by saying if “Germany could not match the United States in terms of private consumption, in the number of cars, radios or refrigerators per household, it did at least boast a vastly greater national stock of combat aircraft and tanks” (Tooze 165). Such waste in creating weapons of mass destruction as a form of invidious expenditure/consumption, is the sacrifice of that which could have been used for human good; it is an expenditure of resources and life energy on that which ineluctably deals out death.

This vicious manipulation of human energy was the talent of the Third Reich and they carefully built it up and unleashed it as an orgy of murder that began in 1938. We are told that: “The violent energy pent up within the Nazi movement during the summer of 1938 unloaded itself not in war, but in an unprecedented assault on the Jewish population. Beginning already in the summer of 1938, the Nazi party orchestrated a wave of anti-Semitic outrages that culminated in a nationwide pogrom on 9 November 1938 [Kristallnacht]…” (Tooze 274). This is the start that witnessed the Jewish population in Germany and surrounding states being turned into the accursed share to be destroyed to serve the goals and satisfy the unholy fantasies of the Third Reich.

But others including the Poles and Russians were also treated as so much that needed to be expended to provide the Lebensraum for Hitler’s Nazi empire. Ultimately, millions were wiped out to serve the unbridled international competitive drive of a virulent Darwinism. So we discover that there was systematic murder of Poles in the early stages of war breaking out; and within “less than a year of the outbreak of hostilities, murderous violence had thus become an officially sanctioned element in the management of the German war effort…[T]he management of the food supply…went beyond selective purges to adopt a more comprehensive policy of genocide” (Tooze 365). And indeed, it was the fear of not having enough food and resources as much as megalomania and the need to be number one at all costs and the winner in everything that drove the Nazi paradigm of destruction: The Nazi’s genocidal visions were underscored by this as much as it was infected by the virus of racism.

In the case of its conflict with Russia, the Nazi’s initiated —

…a gigantic campaign of land clearance and colonization, which also involved the ‘clearance’ of the vast majority of the Slav population and the settlement of millions of hectares of easternLebensraum with German colonists. Complementing this long-term programme of demographic engineering was a short-term strategy of exploitation, motivated by the ‘practical’ need to secure the food balance of the German Grossraum. The attainment of this entirely ‘pragmatic’ objective required nothing less than the murder, by organized famine, of the entire urban population of the western Soviet Union (Tooze 463).

And this was only the beginning. There was a plan in place to forcibly starve people to death as a sacrifice for the Nazi’s to act out their perceived need for survival and domination: “This genocidal plan commanded such wide-ranging support because it concerned a ‘practical’ issue, the importance of which, following Germany’s experience of World War I, was obvious to all: the need to secure the food supply of the German population, if necessary at the expense of the population of the Soviet Union” (Tooze 477).

Not only were the Soviet people regarded as a ‘surplus population’ of millions, but Himmler addressed the SS on the oncoming ‘race war’ which “would be a fight to the death in the course of which ‘through military actions and the food problems 20 to 30 million Slavs and Jews will die’” (Tooze 479). And Goering claimed that “the starvation of 20 — 30 million Soviet citizens was an essential element of Germany’s occupation policy” (Tooze 479-480). The murder of 20 to 30 million people is discussed as just that much chattel to be thrown on a bonfire to create space for a eugenically superior occupation. There was clearly a quota to be met as part of the calculated killing of human beings to satisfy some form of a five-year death-plan coupled with the projection of economic growth and empire building. But Nazi innovation in destruction did not stop there. They also tried to crudely refine the idea of working people to death.

Jews in the Soviet Union were murdered by the hundreds of thousands in the most brutal fashion. In horror we further learn that in “…Galicia, where it is estimated that as many as 500,000 Jews were killed in the course of the German occupation, shooting and gassing were combined, as Heydrich had intended, with ‘destruction through labour’ (Vernichtung durch Arbeit). The opportunity for the latter was provided by the construction of a major strategic highway necessary to secure the supply lines for Army Group South” (Tooze 481).

However, there can never be too much of a vicious thing for the Nazis, so the Wehrmacht did its best to systematically starve its prisoners to death:

December 1941…the prisoner count had reached 3.35million. Of these, only 1.1 million were still alive and only 400,000 were in sufficiently good physical state to be capable of work. Of the 2.25 million that had died, at least 600,000 had been shot, falling victim to the Komissarbefehl, which gave the German army and the SS Einsatzgruppen the licence to execute any Soviet citizens thought to be politically dangerous. The rest died of ‘natural’ causes. Six hundred thousand died between December 1941 and February 1942 alone. If the clock had been stopped in early 1942, this programme of mass murder would have stood as the greatest single crime committed by Hitler’s regime (Tooze 482-483).

People were just surplus to be expended in any manner that pleased the Nazis. The combination of work and destruction as the ultimate form of murder of the worker was sublimated in the form of concentration camps. For we are told that,

Of the 1.65 million inmates of concentration camps employed at one time or another in the German economy – referring here to camps not involved in the extermination phase of the Final Solution – no more than 475,000 survived the war. This implies the death of at least 1.1 million workers, at least 800,000 of whom do not also number amongst the victims of the Holocaust. Of the 1.95 million Soviet prisoners of war who are thought to have been employed in Germany after November 1941, less than half survived the war. As many as a million Soviet prisoners may, therefore, have died after they were designated as potential contributors to the German war effort. This is in addition to the 2 million who had starved to death over the winter of 1941-2. Of the 2.775 million Soviet civilians who were recorded as working in Germany between 1941 and 1945, it is estimated that at least 170,000 died during their time in the Reich (Tooze 523).

This destruction was only the tip of the iceberg for we learn that thousands of Polish workers and Italian prisoners were also starved and worked to death. Deaths from forced labour for non-Jewish-worker victims amounted to possibly 2.4 million. And as Tooze explains, that number added “to the figure of at least 2.4 million potential Jewish workers we arrive at a total of 4.8 million workers murdered by the Third Reich after it confronted the military crisis of 1941-2, closer to 7 million if we include the Soviet prisoners of war killed in 1941″ (Tooze 523).

When pondering the monstrous violence behind these numbers, we are given a new perspective on Marx’s idea of the reserve army of labour. It is not just a pool from which workers are exploited through low wages, nor is it only a group whose surplus value is robbed and from whom profit is ripped out of. The point is that for the elite to survive within their comfort zones they need the destruction of the reserve army of labour – quite literally. People need to be culled.

The idea of consumption was employed as an image for consuming human life too where the Nazis were concerned. While “Hitler made a particular point of stressing the importance of the Ukraine for Germany’s food supply. Goebbels for his part coined a new propaganda line. Germany, he declared, was ‘digesting’ the ‘occupied territories’” (Tooze 548). Indeed, the expenditure and waste were very much the Nazis willingly going through the act of chewing up humans and spitting out heaps of corpses: Cannibalism as the ultimate form of consumption.

F. Violent economics and that little thing called money

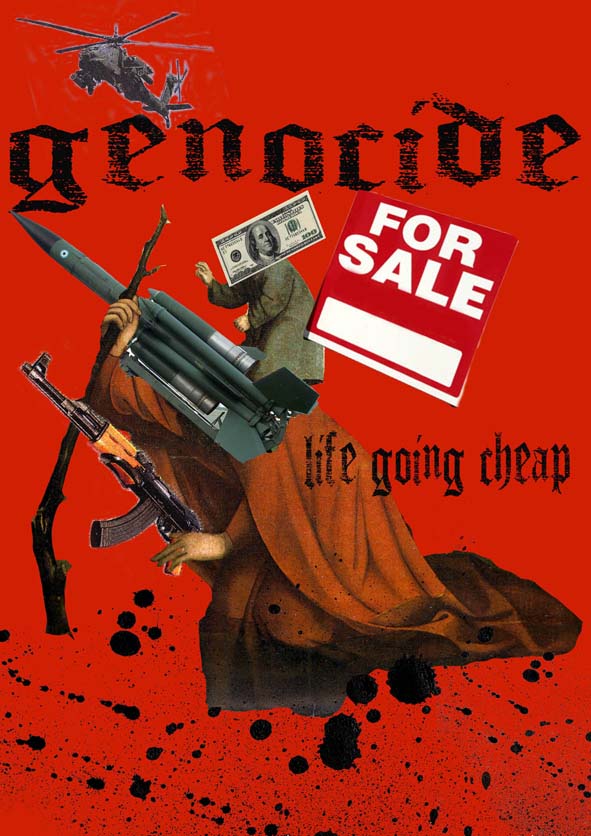

As we have seen there has largely been the channeling and misuse of energy and resources in economies that could have been used to generate abundance, but are used instead for production that involves unconscionable waste of resources and life forms. There is a framework of duality and polarity in which one group extracts from another mercilessly. The extraction of resources from the planet and all life forms results in an inordinate accumulation and hoarding of resources and wealth that is redistributed primarily amongst those who already have plenty. It is a form of waste and expenditure of the most conspicuous, ostentatious and scurrilous kind. This activity for the need to hoard also stems from a mentality of lack which cannot see beyond the veil of self-interestedness, and so imagines and executes various ways of accumulation at the expense of others. This scenario then creates vast imbalances that generate the ‘haves and have-nots’, class structures and hierarchies of authority and control — or, life as we know it.

Inevitably such polarity produces binary ways of existence the pathological symptoms of which include: You are either for or against something, you are either with the winners or are one of the losers, you are either the elite or you are not, you either deserve to live or die. It also creates situations in which conflict and competition for resources not only lead to more destruction, but also involve a harnessing of life energy and resources into the materiel of war, and the horrendous sacrifice of human beings, other life forms and resources of the planet to allow for more capture, creation and accumulation of wealth for the few. It is an unsustainable paradigm of immediate and potential (stored/accumulated) gratification based on the fear of scarcity. It is also predicated upon the fear of death.

This fear goes on to formulate theories and justifications to rationalize extraction and accumulation which only go on to create more waste and less productive or proper use of resources and life. Witness the widespread political and media support for neo-classical economics and capitalism. The only endgame in such a scenario is self-destruction for most as the increasing use of limited fossil fuels and extensive waste of resources to support the well-off and manipulators of the economy instigate further resentment that turns into uprisings and finally conflict. But the missing link here, as is always the case in much analysis of why there is waste and why capitalism and the current economic paradigm plaguing the planet is a one-way street to self-immolation, is – money.

Money is an invention and tool; it is not just filthy lucre. It is also more than merely a means of exchange or a form of mediation to replace barter systems. Money is a means of control. The principal means or tool used to measure economic growth in a system based on perceived lack, competition, excess, waste, destruction, and being able to shift resources, or forge support for one faction over another — is money. The banking and financial elite who control and are the source of money creation, manipulate governments and economies of the day. The orchestrated move away from a gold standard and the monetary discipline it imposes, allows for the creation of lasciviously loose credit via fiat currencies and the corresponding fictitious capital generating scheme of fractional reserve banking.

This not only makes governments, states and peoples dependent on money and those who manipulate it, but their productive capacities and the growth of economies are influenced, often quite negatively, by the flow and disruption of the money supply. The manipulation of money by banks, financial activity, how and where it flows to and is siphoned away from; its accumulation and deployment to produce the results desired by those who wield it legally and more often otherwise – is the underlying force of economies. The so-called productivity of the workforce in our time is dependent on how money is used as a device and weapon to either bring some form of stability or disruption to an economy.

Which then brings us to what such money is called when it is used as a means of shaping and ruining economies and states: It is called Capital. This is the central issue that underlies Marxian thinking. Marx was right in asking that all-important question that is the bedrock of his work – what indeed is Capital. A good contemporary insight into this is provided by Bichler and Nitzan in their Capital as power (a link is provided in the reference list below where the book can be read). Their take on Capital is worth pondering over as they show how it is used as a means of sabotage and an implement for creating systems according to the wishes of those who manipulate it.

The Nazis and all corporate and political war mongers of the world could only unite via Capital. It is the principal weapon of choice that has allowed them to not only manipulate people and states through wages, but to wage destruction and waste resources and life such that people are kept down in fear and controlled: And purged when necessary.

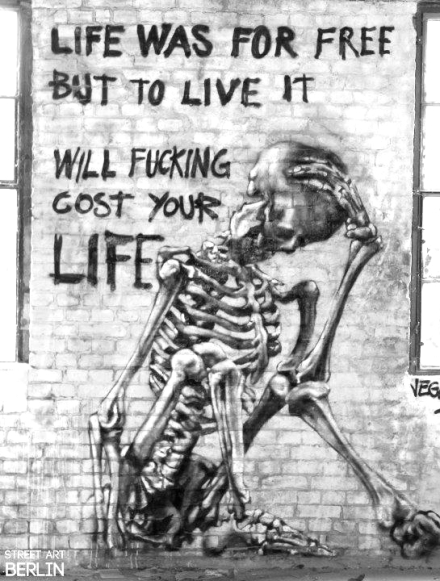

The bottom line is this: You have to be able to pay to live, otherwise you have simply earned your right to die. The forces of economic violence enhanced as capitalism is also a form of market euthanasia. The teaching of occult economic theories will always be supported, if not sponsored, by corporations and big finance in so-called elite universities that will continue to produce automatons and moral decrepits who promulgate further theories of social and economic violence that are used to cull the populace of the world. That is, enough people on the planet must be left to allow for the social reproduction and maintenance of the elites and socio-politico-economic controllers – this is the highest form of the lowest moral standards in human exploitation and subservience. Enough people must also be there to socially reproduce themselves (as the wage-slaves that they are) as the fodder that keeps the elites alive. Excess baggage is to be terminated through war and violent economics and whatever hardships disease and starvation can bring.

Violent economics is meant to create and order the world into a death camp. The concentration camp is as much a microcosm of our lives, as much as the world is designed to be a concentration camp writ large. This is the final goal of capitalism.

But still the central question of Marx remains unanswered: What truly is Capital? It can be used as power and it is used as a means of exploitation and devastation, but how is this possible as such? How is money, something we are familiar with, transformed into Capital and become that which has been used to manipulate and destroy life and in the process the well-being of the planet itself. This is the principal idea that is explored in subsequent pieces through which — it is hoped — it will be clearer what Capital is and how and why it is an expression of power.

References:

1. Bataille, Georges. “The notion of expenditure”, Visions of excess: Selected writings, 1927-1939. Trans. Allan Stoekl, Carl R. Lovitt and Donald M. Leslie, Jr., University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 1996.

2. –. The accursed share, vols. 1-3. Trans. Robert Hurley, Zone Books: New York, 1998 (vol.1), 1999 (vols. 2 and 3).

3. Bichler, Shimshon and Nitzan, Jonathan. Capital as power: A study of order and creorder, Routledge: London and New York, 2009. The book can be read here: Link

4. Engels, Friedrich. The condition of the working class in England. Ed. Victor Kiernan, Penguin Books: London, 2005.

5. Hudson, Laura. “The political animal: Species-being and bare life”, pp 18-30, Left Curve, No. 35.

6. Linebaugh, Peter. The London hanged, Verso Books: London, 2006.

7. Marx, Karl. Grundrisse. Trans. Martin Nicolaus, Penguin Books: London, 1993.

8. –. Capital, Vol. 1. Trans. Ben Fowkes, Penguin Books: London, 1990.

9. Tooze, Adam. The wages of destruction: The making and breaking of the Nazi economy, Penguin Books: London, 2007.

10. Veblen, Thorstein. The theory of the leisure class, Dover Publications: New York, 1994.

The writer is the editor of Philosophers for Change.

If publishing or re-posting this article kindly use the entire piece, credit the writer and this website: Philosophers for Change, philoforchange.wordpress.com. Thanks for your support.

One Comment

Comments are closed.

Reblogged this on A Green Road Daily News.